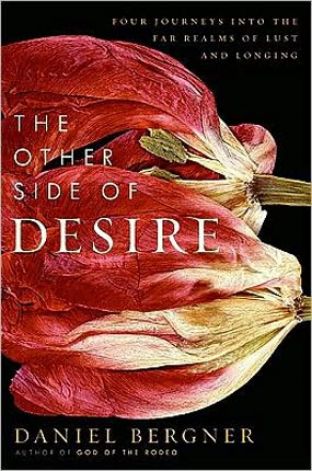

Tragedy is full of forbidden desires: the love of Phaedra for her stepson Hippolytus; of the dying Aschenbach for the beautiful Tadzio; of Martin Gray for his goat in Albee’s play. In tragedy, so in life. Daniel Bergner’s The Other Side of Desire: Four Journeys Into the Far Realms of Lust and Longing (HarperCollins, 2009) describes a series of intense, unorthodox and in some cases forbidden lusts, many of which have the stamp of the tragic. There’s Roy, who couldn’t resist his twelve-year-old stepdaughter. Jacob, for whom women’s feet “were the breasts, the legs, the buttocks, the genitals”. The Baroness, an East Village dominatrix who once literally spit-roasted a man for three and a half hours. Ron, an advertising artist drawn erotically to amputees. In the course of his sexual odyssey across America, in which he meets a Kinseyan gallery of fetishists, sadists, masochists, psychiatrists and sex offenders, Bergner explores possible answers to big questions:

Tragedy is full of forbidden desires: the love of Phaedra for her stepson Hippolytus; of the dying Aschenbach for the beautiful Tadzio; of Martin Gray for his goat in Albee’s play. In tragedy, so in life. Daniel Bergner’s The Other Side of Desire: Four Journeys Into the Far Realms of Lust and Longing (HarperCollins, 2009) describes a series of intense, unorthodox and in some cases forbidden lusts, many of which have the stamp of the tragic. There’s Roy, who couldn’t resist his twelve-year-old stepdaughter. Jacob, for whom women’s feet “were the breasts, the legs, the buttocks, the genitals”. The Baroness, an East Village dominatrix who once literally spit-roasted a man for three and a half hours. Ron, an advertising artist drawn erotically to amputees. In the course of his sexual odyssey across America, in which he meets a Kinseyan gallery of fetishists, sadists, masochists, psychiatrists and sex offenders, Bergner explores possible answers to big questions:

How do we come to have the particular desires that drive us, how do we become who we are sexually, whether our lusts are common or improbable? How much are we born with and how much do we learn from all that surrounds us, how much can we change and how much is locked unreachably, permanently within?

Nature-nurture is a key fulcrum. Often Bergner is able to unearth an origin, a pop-psych explanation for the paraphilia (love or desire that exceeds the bounds of the so-called normal) that he encounters. Jacob, for instance, struggled at school and some speculate that his floor-gazing shame in the classroom was transmogrified by the anarchic hormones of puberty into an erotic attraction to what he found there, namely feet. He later met his first girlfriend while selling shoes in a sports apparel store. But can these biographical tidbits account for the extraordinary, overwhelming erotic charge that feet carry for him? This is a man who was unable to listen to the winter weather report because talk of snowfall (measured, of course, in…) would arouse him so much and who could achieve orgasm without genital contact just by looking at feet.

Bergner wisely entertains all possibilities. He meets Baltimore psychiatrist Fred Berlin, who was an expert witness in the trial of Jeffrey Dahmer and who has a fatalistic view of desire: paraphilias are most likely hard-wired and, especially in the case of the more dangerous varieties, can only be controlled chemically. Others are even more scornful of nurture. In the Baroness’s basement, a middle-aged man attached genitally to a machine programmed to give him electric shocks at the sound of voices mocks Bergner when he asks about his childhood: “I was never raped by homosexual dwarves.” Meanwhile, research conducted by Ray Blanchard and James Cantor into paedophilic tendencies suggests that they are programmed prenatally. As with tragic heroes, is it then fate that guides sexuality down the road less travelled?

Bergner wisely entertains all possibilities. He meets Baltimore psychiatrist Fred Berlin, who was an expert witness in the trial of Jeffrey Dahmer and who has a fatalistic view of desire: paraphilias are most likely hard-wired and, especially in the case of the more dangerous varieties, can only be controlled chemically. Others are even more scornful of nurture. In the Baroness’s basement, a middle-aged man attached genitally to a machine programmed to give him electric shocks at the sound of voices mocks Bergner when he asks about his childhood: “I was never raped by homosexual dwarves.” Meanwhile, research conducted by Ray Blanchard and James Cantor into paedophilic tendencies suggests that they are programmed prenatally. As with tragic heroes, is it then fate that guides sexuality down the road less travelled?

Greg Lerne, another sexologist Bergner encounters, inclines towards the nurture side of the debate: “The lovemap cartographic system may operate like a multi-sensory camera that episodically takes photos of the immediate environment and stores them as depictions of the sexual terrain”. Many believe this lovemap can be redrawn, boosted by evidence from cognitive behavioural therapies and experiments with anti-androgens which suppress the sex drive, typically inhibiting the most exotic desires first. Indeed in some cases, patients are able to enjoy a sex life free of paraphiliac tendencies after a finite treatment of these drugs. On the other hand, the drug argument seems to lead, Möbius-style, back to the nature view. The serial killer Michael Ross was able to feel remorse and pity for the families of his victims only after he had been chemically castrated, which if nothing else suggests that it was principally his chemical make-up that compelled him to rape and kill in the first place.

Bergner writes dispassionately, mostly unmoved by the brutal sadomasochism, convicted child molesters and people who prefer horses whom he encounters. This lends a great deal of credibility to his analysis, which takes care to give as rounded a picture as possible. What one might find tragic about some of these cases — people wracked by desires that are inescapable and in some cases irreconcilable with a fully functioning social existence — is made so through Bergner’s generous and broad-minded approach. Here he is talking about why a reader’s discomfort may not be a bad thing:

The last part, “The Devotee”, is hopeful. Ron grows up erotically obsessed with disabled women. “For dates he chose the kinds of girls his friends desired. Pressed against them, ‘I closed my eyes and imagined that they didn’t have a leg or an arm.'” In another part of America, Laura is in despair after losing both her legs in a car accident. The story of their love lifts the book out of the darkest recesses of earlier sections and vindicates a comment made earlier in the book by psychoanalyst Muriel Dimen: “Perversion can be defined as the sex you like and I don’t”. The odds may be against you if your thing is feet or the lack thereof, or if having a V carved into your back is what gets you going. But when you find love, Bergner’s question is simple: how can it be wrong when it feels so right?

Daniel Bergner will be talking about his latest book, What Do Women Want?: Adventures in the Science of Female Desire, at our next Seriously Entertaining show, “In Case of Emergency”, at City Winery NYC on April 28. You can buy tickets here now. Also, follow Daniel on Twitter here.