The Bookmobile for Fifth of July

On Saturday, July 9, the SpeakEasy Bookmobile visited Weeksville Heritage Center at the border of Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy, in celebration of the Fifth of July. Fifth celebrations date back to 1827, when Black New Yorkers joined in church, parade, and other public gathering spaces to mark the legal abolishment of slavery in the state of New York. Described to me as being “to New Yorkers what Juneteenth is to Texas,” I felt grateful to be able to be a part of this year’s event through the Bookmobile’s presence. The day’s festivities included tours of the Center’s on-campus Hunterfly Road Houses as well as MacShack’s creamy homemade mac n’ cheese, chicken wings, and fresh lemonade distributed from a geranium-pink truck.

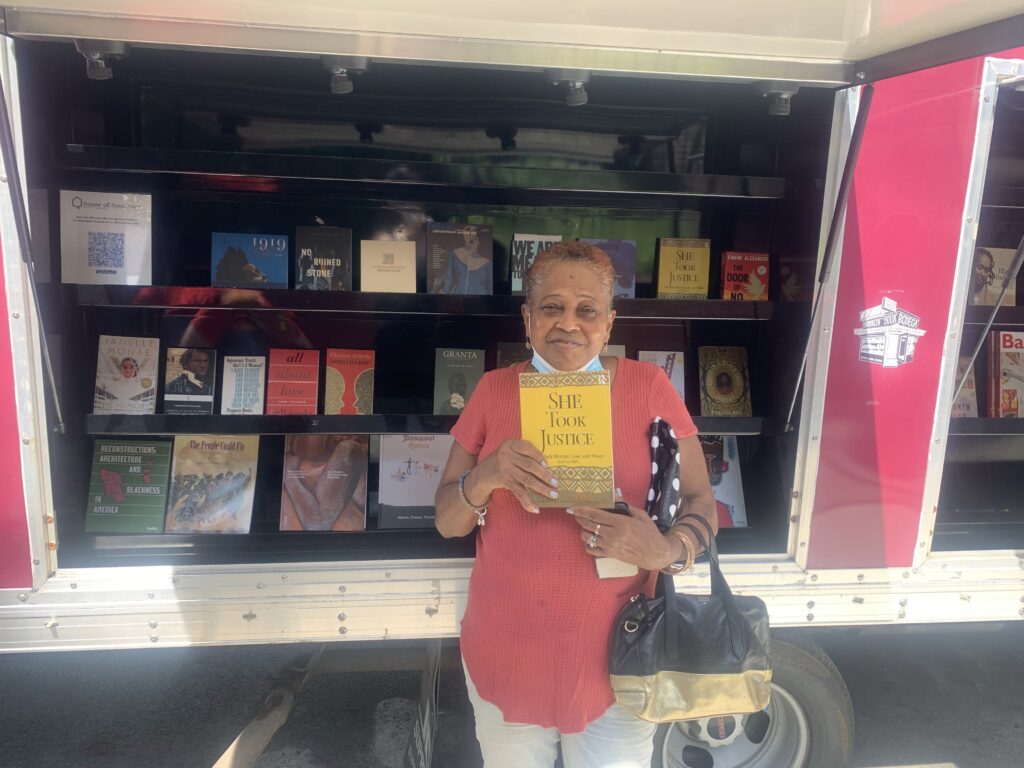

Ms. Deutchin of Crown Heights with 2021 Routledge publication She Took Justice, a history of Black female resistance through a legal framing. The text intimately chronicles stories of Black women from Queen Nzinga Mbande (1583 – 1663) of present-day Angola, to Mary Jackson (1921 – 2005), NASA’s first Black female engineer.

While the Juneteenth weekend festivities in which SpeakEasy participated were overwhelmingly celebratory, the Center—which orients itself around an axis of liberation built on “Weeksville’s radical history of freedom, autonomy, and preservation,”—consciously structured their Fifth of July as a day of both joyful recognition and contemplation. I kept this in mind as I curated titles for the Bookmobile’s shelves. The day’s selections featured a generous spread of art and theoretical books centered on artists of the African diaspora: Basquiat-centered works; a title from a 2021 Biennale exhibition on Chicago-based artist collective AfriCOBRA, Relations — Diaspora and Painting; and a collection of works by Congolese sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez, among others. Somebody who specifically sought the hardcover catalog for a 2021 MoMA exhibit, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, was able to find it on our shelves. I was also sure to stock memoirs, including Aftershocks by Nadia Owusu, Black Indian by Shonda Buchanan, and The Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward (I’ve found Ward’s work to be stunning, fiercely compassionate, and forceful; you can also read her here).

During our stay on Buffalo Ave, we were visited by community members who call this corner of Brooklyn home. Author and NYU Professor Dina C. Tate, an ebullient woman dressed in black, was excited by the sight of the truck; an hour or so later, she returned, two copies of her own book in hand: Lizzie & McKenzie’s Fabulous Adventures: Mayhem in Madrid, which she donated to our shelves.

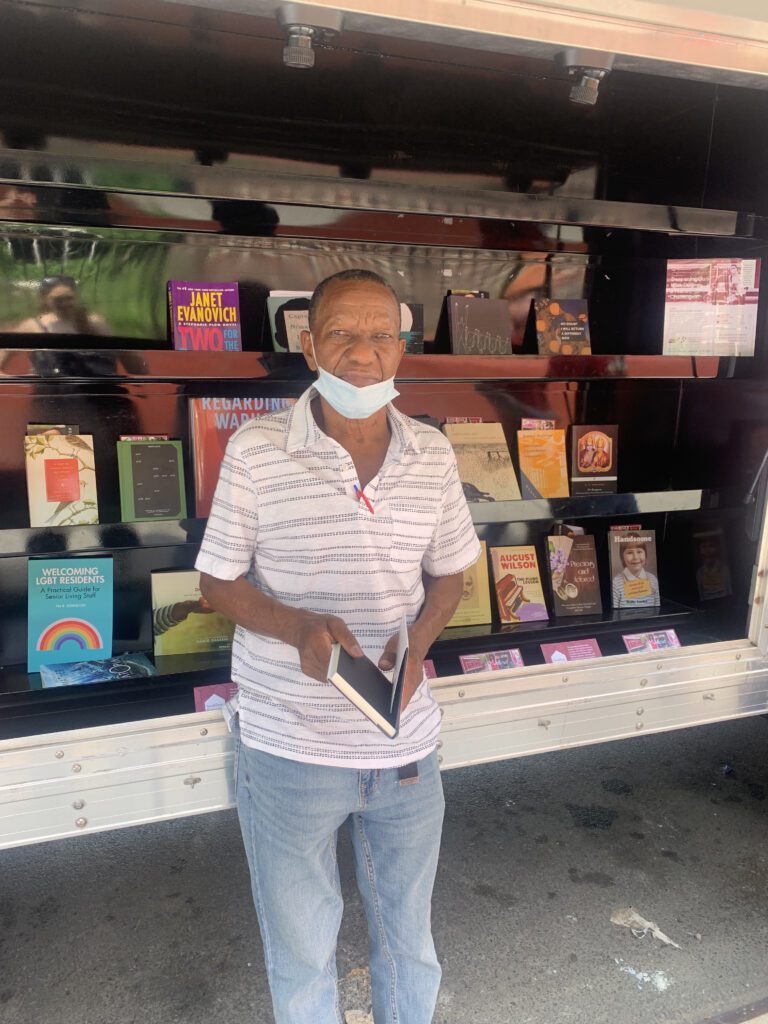

Mr. Johnson of Crown Heights holding a book of texts from Cicero who, per the book’s introduction, had “a deep longing to know about the role of gods in earthly life. “

We also met Lorraine Deutchin, who requested books for her two granddaughters, Arianna and Arschael, 12 and 10 years old, respectively: “They love reading the big books. Sometimes Arianna comes by me, she says: ‘It takes you so long to read this! Let me read it.’ Sometimes, the print is too small, and she reads for me. I’m looking for educated stuff.” She left with a gentle grin on her face and a copy of Dr. Gloria J. Browne-Marshall’s She Took Justice: The Black Woman, Law, and Power — 1619 to 1969, which she said that Arianna would devour.

An elderly man with a furrowed brow, broad features, and close-shaved head stopped to speak with us. “Kenneth Johnson,” he told me with a steady gentleness when I asked his name. “Something to do with philosophy,” he replied when I asked if I could help him find anything. I handed him a copy of How to Think About God: A Guide for Believers and Nonbelievers, a collection of Philip Freeman’s translations of Cicero’s canonical Stoic texts On the Nature of the Gods and The Dream of Scipio. He flipped through it, commenting as he went: “I want to know so many things. I want to know, know, know, know. I just can’t learn enough…. In school, the teacher asked me, ‘What makes you happy?’ I did not know what to write. The things that used to make me happy don’t make me happy anymore, things that made me unhappy don’t anymore.”Is anything, I wondered, certain for a man who questions everything? For Mr. Johnson, the answer is “yes”: quite simply, faith. “Wherever I am, God must be there at all times,” Johnson told me plainly with quiet assurance.

Also on the Bookmobile’s shelves, although short-lived due to its popularity, was a copy of Frederick Douglass in Brooklyn, a collection edited by Theodore Hamm, including eight of Douglass’ speeches delivered in Brooklyn. Not included here, however, is the speech with which, more than any other, Americans associate today with the Fifth of July: Douglass’ “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” given in 1852 at Corinthian Hall in Rochester and meant to mark that year’s Independence Day celebration. Per Douglass, for the Black person in America, the hypocrisy and falseness of Fourth of July festivities is stark. Douglass’ speech is severe and boldly honest, while asserting a faith in human agency with language that is as relevant today: citing a psalm credited to poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Douglass proclaimed: “My business, if I have any here to-day, is with the present … ‘Act, act in the living present … ’” He continued: “Your fathers have lived, died, and have done their work, and have done much of it well. You live and must die, and you must do your work.”

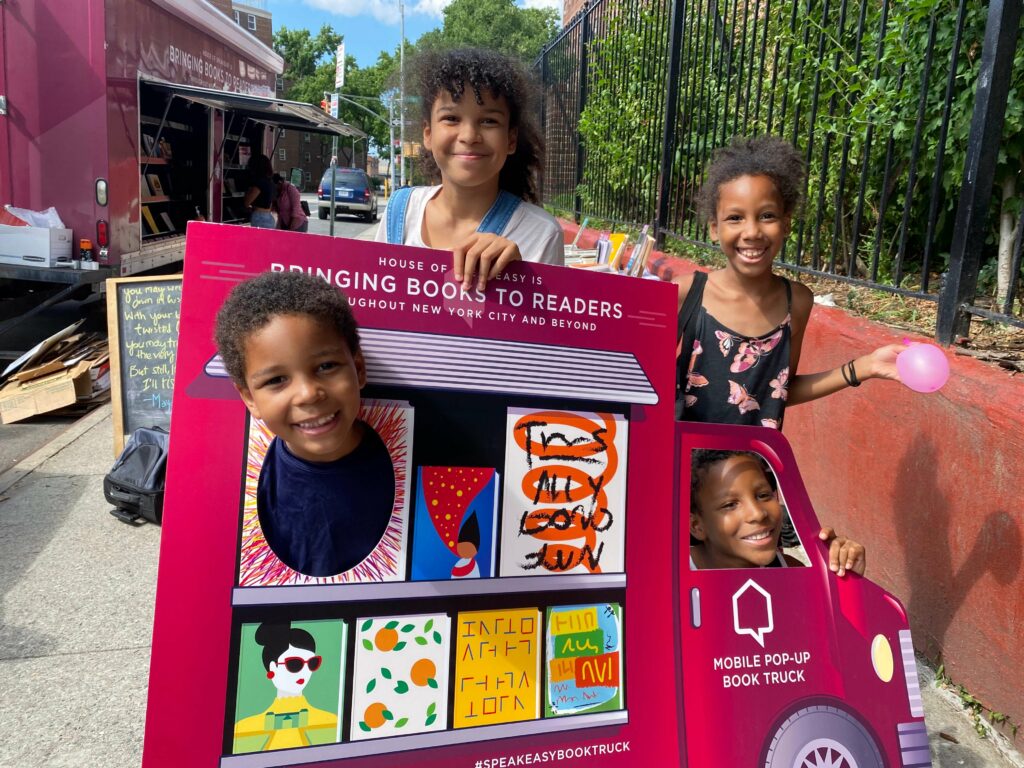

Standing by the Bookmobile, I found myself wondering, What exactly does this “work” look like? I watched as a group of children huddled over a book they had pulled off the shelves and found the beginnings of an answer: in books, and in the community of others.

Ryan Tuozzolo is a writer living in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Contact her at [email protected].