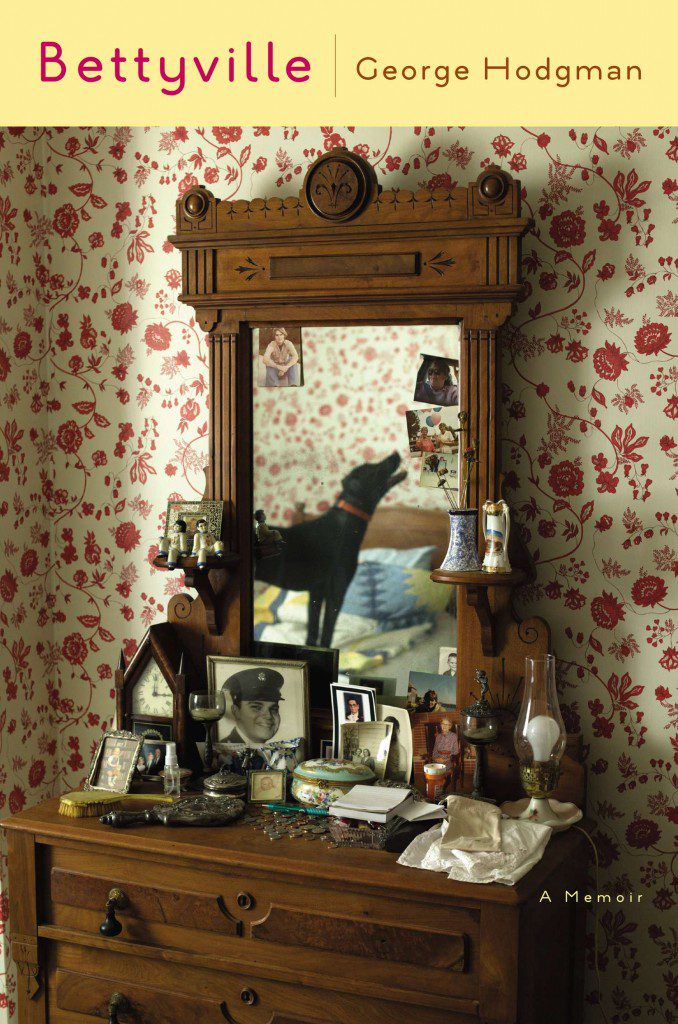

Bettyville: A Memoir

George Hodgman

Penguin Publishing Group, 2015; 288pp

In the sub-genre of literature about the poisoned relationships between mothers and their gay sons, George Hodgman‘s Bettyville is an instant classic. Constantly funny, occasionally pointed, it is distinguished particularly by its warmth and its author’s uncommon empathy. At its heart, Bettyville is a carefully calibrated understanding of (rather than attack on) how other people live.

George Hodgman was an editor at Simon & Schuster and Vanity Fair before he upped sticks from his New York City life and moved back to Paris, Missouri, to look after his ninety-year-old mother. Betty Hodgman had lived for many years in Paris in almost total ignorance of her son’s life, relationships, and struggles. Returning to Missouri unlocks all kinds of memories for George, which he sprinkles into accounts of his new daily life with his mother. Betty, despite retaining a sharp, reprimanding tongue, has begun to exhibit signs of dementia and becomes increasingly though reluctantly dependent on him (“Clearly I am, in her mind, the Joan Crawford of elder care”). Around the edges of this picture live the folks back home — Hodgman relations, high-school friends and foes, the congregation at Betty’s church — and a stray dog that George toys with adopting.

The book’s sustained comic tension lies in the philosophical differences between George and his mother. “I am irony,” he writes. “She is no nonsense. Our lives have been lived on different planes.” “You’re not as funny as you think you are,” Betty tells him, often, reminding us that it’s not that she doesn’t get what he’s saying; she simply doesn’t appreciate it. Perhaps because of their even match, and despite occasional asides — Betty’s house is “the last place in America with shag carpet” — Hodgman doesn’t sneer at his mother. Nor are his observations of life at large in Missouri those of a typical city-slicker-come-home, although he does observe moments of acute provincialism:

Camilla, Jane’s sister, who has worked construction all over the world, including in Iraq, talks about Baghdad. The city, she says, barely exists now.

“Just like here,” remarks Evie. “Stoutsville is just gone. We had banks, stores, a restaurant, even a movie theater. And the trains. Every time I heard the whistle, I’d run down to the tracks to wave at the engineer. In summer, the gypsies would come and steal everything. They wore bright colors and drove old cars. Mama would tell us to get under the bed when they were around. People said they liked to run off with children.

“There’s not a kid here anybody’d take now.”

These moments, which usually go unremarked (though their very inclusion is telling), are balanced by Hodgman’s rediscovered appreciation for the kindness of people back home: “such kindness, the casserole on the doorstep from someone who does not expect to be acknowledged, the wet morning flowers in the mailbox”. Although there’s an awful lot of sadness in Bettyville, there’s very little bitterness. It seems George’s escape into city life never completely effaced his familial affection for the people back home.

Hodgman’s wit is the very texture of Bettyville; it’s in every sentence. When faced with his first fishing trip, one of his parents’ many failed attempts to interest him in typical boyish activity, he remarks, “I was no Huck Finn, though I thought the hat was interesting.” When the fish don’t come: “‘Daddy,’ I said, ‘you know and I know that this is just a shit waste of time.'” They go see Funny Girl instead: “I did not know Barbra Streisand, but anyone who tripped on her pants leg at the Oscars was my kind of person.” Like David Sedaris, he’s self-deprecating and neurotic and fabulous and extravagant. Depressed by his new life with Betty, he writes, “I wish I were on drugs. Yesterday at the meat counter when they asked what I needed, I whispered to myself, ‘Xanax. And a little crack on a bagel.'”

Hodgman’s wit is the very texture of Bettyville; it’s in every sentence. When faced with his first fishing trip, one of his parents’ many failed attempts to interest him in typical boyish activity, he remarks, “I was no Huck Finn, though I thought the hat was interesting.” When the fish don’t come: “‘Daddy,’ I said, ‘you know and I know that this is just a shit waste of time.'” They go see Funny Girl instead: “I did not know Barbra Streisand, but anyone who tripped on her pants leg at the Oscars was my kind of person.” Like David Sedaris, he’s self-deprecating and neurotic and fabulous and extravagant. Depressed by his new life with Betty, he writes, “I wish I were on drugs. Yesterday at the meat counter when they asked what I needed, I whispered to myself, ‘Xanax. And a little crack on a bagel.'”

The drug references — there are many others — turn out to have a hard edge. “It took a lot of drugs for some of us to feel free,” Hodgman writes in one of the passages dealing with his own substance-abuse struggle, a corollary to his sexuality struggle. In New York, there are all-night sessions in clubs followed by early-morning calls to dealers. Ragers on Fire Island. A week spent editing a book on speed. For Hodgman, drugs are a direct consequence of his shame. They allow him to be both with people and alone; they fill his silences with music. As a teenager, the night his mother found issues of The Advocate under his mattress changed everything and set the pattern for what would come:

This was the beginning of many silences to follow, our struggle with words. At the time, I thought the silences, the secrets did not matter. As it happened, they did. This is what I have learned: To build a life on secrets is to risk falling through the cracks. “Shame is inventive.” I read this in a book somewhere awhile back and it has haunted me for years. Shame can make a joke. It can reach for a bottle. It can trip you up when you don’t even know it is there. It can seep into everything without your ever knowing.

“Doesn’t it feel a long way from home?” a friend remarks to George after a drugged-out night on Fire Island. The sense of being an outsider, often a consequence of silence as much as explicit rejection, can be extremely damaging. Hodgman’s wit never lets up, but it’s laughter in the dark:

When he [Hodgman’s therapist] asked if I used drugs, I said only when they were available. He asked if they were a problem. I said not for me. He said I should not use them as an avoidance. Why else would I use them?

“You don’t have to entertain me,” he said.

“Then what are you paying me for?”

“You are hiding from your feelings.”

“Can you teach me how to hide a little better?”

“Why did you come here?”

“Lobby art.”

“Why did you come here?”

“Because I can’t get a job.”

Irony is Hodgman’s defense in the face of a hostile world.

But there is also a richness to the so-called “gay experience” that arises out of its challenges. In one extraordinary chapter, Hodgman recalls the evening of his college commencement, when Betty and Big George, his father, joined him and Steven, his senior-year boyfriend (though unacknowledged as such), at the best restaurant in town. Near the end of the meal, Big George got up, strode over to the pianist playing in the corner of the room and started to sing “Old Man River”. “He sang emotionally,” Hodgman writes, “his waves of feeling flowing through us all… My emotions built with his every word and breath.” It’s a surreal, cinematic moment, dense with interpretative possibility: “I didn’t know whether to consider it a blessing, a resentful usurping of the prominence of others that evening, or a crying out as the river’s waters swept me from his world, his extended hand, the place where it was possible for him to try to save me.” These moments of polysemy are common in gay life, where language and social cues are often ambiguous, where gestures might telegraph any number of emotions that words aren’t up to. Hodgman finds a kind of salvation in these moments. And in his last months with Betty, they accumulate. Though there’s no Oprah-atic epiphany, there’s a gradual thaw between the two of them that arises out of his expanding idea of his mother and her life.

Hodgman’s editing career has served him exceptionally well. Bettyville is a concise, tightly written book, a light breeze over profound depths, in which familiar material is imbued with a heartbreaking particularity. It’s a work of consolation and healing, rare indeed in a book that’s also genuinely hilarious.

George Hodgman will appear at the Seriously Entertaining show It’s Not You at Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater on March 7, 2016. Buy tickets here.