Prefatory note: strongly recommend you watch Boyhood without seeing the trailer or doing a Google Image search or anything like that. Probably don’t read this yet either. But the bottom line is, do see it.

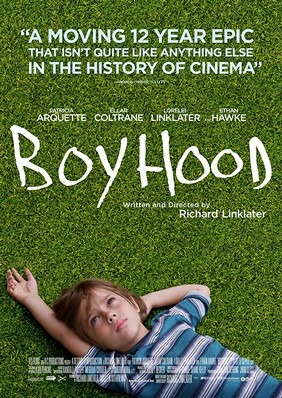

Blue sky, white clouds, the opening chords of Coldplay’s “Yellow”, the handwritten title (in black): Boyhood. Reverse shot: Mason Jr. (Ellar Coltrane), aged six, lying flat on the grass, his right arm thrust straight up above him, his left hand behind his head, staring up at the sky. What’s in his mind is a mystery, though it becomes clear that he enjoys the incidental pleasures of childhood like any other boy — computer games, graffiti, underwear catalogues, biking through the suburbs, Harry Potter at bedtime. Chris Martin starts to sing: “Look at the stars / Look how they shine for you / And everything you do.” It’s a song about unrequited love, here repurposed, perhaps, as a hymn from director Richard Linklater to his unconventional muse. When I saw Boyhood at BAM, Linklater and Coltrane spoke briefly beforehand, and the director compared casting Mason Jr. to selecting the next Dalai Lama. “What I liked about Ellar,” he said, “was that he kinda didn’t give a shit what you thought. This kid was gonna go his own way.”

Blue sky, white clouds, the opening chords of Coldplay’s “Yellow”, the handwritten title (in black): Boyhood. Reverse shot: Mason Jr. (Ellar Coltrane), aged six, lying flat on the grass, his right arm thrust straight up above him, his left hand behind his head, staring up at the sky. What’s in his mind is a mystery, though it becomes clear that he enjoys the incidental pleasures of childhood like any other boy — computer games, graffiti, underwear catalogues, biking through the suburbs, Harry Potter at bedtime. Chris Martin starts to sing: “Look at the stars / Look how they shine for you / And everything you do.” It’s a song about unrequited love, here repurposed, perhaps, as a hymn from director Richard Linklater to his unconventional muse. When I saw Boyhood at BAM, Linklater and Coltrane spoke briefly beforehand, and the director compared casting Mason Jr. to selecting the next Dalai Lama. “What I liked about Ellar,” he said, “was that he kinda didn’t give a shit what you thought. This kid was gonna go his own way.”

Watching him go his own way is the remarkable content of Linklater’s film. Filming began in Austin in 2002 and ended in fall 2013. (Huge kudos to IFC Films for funding such a project, especially in the current — dire — climate for experimental film-making.) In the intervening period, the cast and crew reconvened annually to shoot more scenes. Coltrane is in virtually every one of them, and we have the astonishing, emotional privilege of seeing him grow up before us. Most critics have been name-checking Michael Apted’s Seven Up series; some have mentioned Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films; the children of the Harry Potter films are another obvious point of comparison. But Linklater’s achievement is singular. There simply isn’t anything like it in the history of cinema. No other film comes close to representing with such resonance or tenderness cinema’s unique ability to capture the ineffable sadness of time passing. To experience Boyhood is to experience life at an accelerated pace; its unstoppability is devastating.

Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke play Mason Jr.’s parents, Olivia and Mason; Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, is his sister Sam. All are superb. And as with Coltrane, time sculpts them over the course of the movie. They change shape, they gain and lose weight, hair changes colour and length. Twenty-first-century American life happens around them: the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Obama v McCain, Facebook, the financial crisis. But Boyhood‘s use of the conventions surrounding time gives old tropes new flavour. Musical referents — Britney Spears, Vampire Weekend, High School Musical, Arcade Fire — are seemingly used in the same way that filmmakers play KC and the Sunshine Band or ABBA in a film set in the ’70s. A scene in 2008 with Mason and Sam erecting Obama placards in suburban gardens is, likewise, an obvious signpost of time and place. But knowing how the film was made gives these signifiers a different, strange, uncanny power. When they were shot, they were not the kitsch markers they seem now; rather almost documentary. It’s the cinema of nostalgia but with a heightened sense of ephemerality. Like Arquette’s Olivia, who declares that she will spend the rest of her life getting rid of the stuff she spent the first half acquiring, we see that the only things that last — that really matter — are our relationships with the people we love.

Manohla Dargis observed that the film is “set to the rhythm of life“, and this isn’t just critical poetry: the nature of the project dictated it. Detractors, currently almost entirely absent on both Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes, will argue that the final product is kind of plotless and meandering. They will say that Boyhood presents a series of narrative clichés borrowed from soap opera and other realist dramas; that its concept cannot mask the imaginative poverty evident in its parade of alcoholic stepdads, mumblecore pop-culture ramblings, and scene-by-scene inconsequentiality. The shooting and editorial styles are unremarkable, the dialogue contains few surprises, the supporting performances are variable.

But Boyhood transcends cliché, both through its audacious concept and by making a sort of virtue of its low-key approach. Who hasn’t been at a party where someone’s picked up a guitar and started to sing “Wish You Were Here”? There are very few scenes that won’t be immediately familiar to viewers from their own lives: overheard parental arguments, parties, birthday presents, the violence of school life, the tyranny of adults, haircuts, petty disappointments and mindless exuberance. Boyhood isn’t shaped like art and sometimes it doesn’t look like it. But it achieves something that only great art can. It makes one feel intensely, and it’s capable of changing the way one sees both the medium of cinema and the world outside.

One of the great achievements of Boyhood is that it genuinely feels like a careful selection of moments from a much larger story. As Terrence Malick did in The Tree of Life (2011), Linklater discovers the profound in the quotidian. That Mason develops an interest in photography is a neat correlative of Linklater’s ability to take the inconsequential and, by the mere act of selection, elevate it into meaning. And there are many lovely moments to remember. A passed note from a girl in his class that reassures Mason that his new buzzcut (at the hands of his brutal stepfather) looks “kewl.” A fifteen-year old Mason returning home a little drunk, a little high, unashamed to confess his state to his mother. The evident, seemingly unacted affection Coltrane and Linklater have for their onscreen parents. Arquette’s spontaneous and heartbreaking sob the day Mason leaves for college: “I just thought there would be more,” she says.

Boyhood ends with Mason’s first day at college. He, his new roommate and two girls decide to skip the orientation mixer and take a hike in the desert. Mason and one of the girls hit it off, and in the film’s final dialogue they flirtingly discuss seizing the moment. “It’s like it’s always right now,” rambles Mason, delaying the moment of contact. To an extent this is a sort of “meta” statement, for moments captured on film do indeed retain the power to reproduce a now that’s now then. In Boyhood, though, we see cinema exhibiting a power we’ve never seen before. Linklater’s unique filmmaking process effaces the line between fiction and reality, lending his characters a new level of realism. This is partly because ageing simply cannot be acted as well as proved. But it’s also because the actors have shaped the material as much as time has shaped them. The filmmakers are fortunate that in Coltrane they found a boy who’d grow up to be the beautiful, gentle free-thinker we see at the end of the movie. They’re also tremendously blessed by the intelligence, humility and sensitivity of Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette, who, in an understated way, give the best performances of their careers.

Cut to black, and Arcade Fire’s “Deep Blue”. Lyrically, it’s a thoughtful answer to “Yellow”: “Here, in my place and time / And here in my own skin / I can finally begin.” Is this Mason, a boy on the brink of adulthood, discovering freedom for the first time? Or Coltrane, breaking through the fourth wall of a twelve-year performance?

If you’ve already seen it, watching the trailer will likely make you want to see it all over again. But anyway: