“There’s some of us, yourself included I’m sure, have seen and borne witness to a number of terrible things. And as you’ll know, those things haunt a man.”

“There’s some of us, yourself included I’m sure, have seen and borne witness to a number of terrible things. And as you’ll know, those things haunt a man.”

— Klyde in After the Fire, a Still Small Voice by Evie Wyld

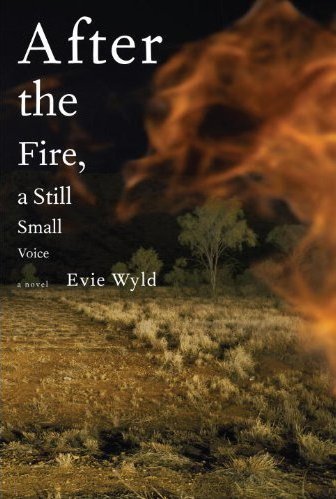

Evie Wyld is the award-winning author of All the Birds, Singing, published by Pantheon earlier this month. Ahead of her appearance at next week’s Seriously Entertaining show, we returned to the past and her harsh, mysterious, brilliant first novel, After the Fire, a Still Small Voice (Pantheon, 2009). Mild spoilers lie herein.

The novel’s title refers to a divine misunderstanding in 1 Kings. The prophet Elijah is camping out on Mount Horeb, where Moses received the Ten Commandments. He complains to God that he’s the last of the faithful. God suggests he go outside onto the mountain, where he stages a meteorological spectacular for Elijah: strong wind; an earthquake; “after the earthquake a fire; but the Lord was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice”. And the voice says to him, “What doest thou here, Elijah?” The prophet repeats his gripe, betraying how little he has learned from this moment of revelation.

It’s an appropriate touchstone, for Wyld’s tale is also one in which signs go unheeded, weather has a divine flavour about it, and despair is best served violent. In it, she follows two characters whose relation only becomes clear about halfway through. In alternating chapters we see (present-day) Frank, who returns to the shack he grew up in with his parents to recover from a disastrous break-up, and Leon, a talented baker forced to follow in his father’s footsteps when he is conscripted to fight in Vietnam. The setting is the east coast of Australia, a snake- and spider-ridden wilderness where even a child knows how to make a fire, how to hold a crocodile, how to spell SOS with flags, who Ned Kelly was and how to kill a chook.

Frank finds his homecoming at once strange and familiar. “He remembered the place feeling more tropical, the soil thicker and wetter”; “the clearing was smaller than he remembered”; “it was darker and smaller than he remembered”; and yet “inside it hadn’t changed, and it made his chest tight to see”. This uncanniness, along with the strange sensation that the shack had been waiting for him, confers an expectant air of reckoning on the setting. Frank can’t bear to see the beds where he and his parents once slept, nor the wedding-cake figurines of his forebears, and sets about doing over the past as he works through his misery at losing Lucy. “The bloody feel of some bastard terrible thing swimming inside him” is one that won’t let up either for Frank or the reader. He soon gets a job dealing in freight and makes friends with neighbours Bob and Vicky, as well as Sal, their hot-headed daughter who turns up one day and suggests he employ her to work on his “farm”. Memories of Lucy haunt him while in the background the news of missing local girl Joyce Mackelly develops in poignant counterpoint.

Frank finds his homecoming at once strange and familiar. “He remembered the place feeling more tropical, the soil thicker and wetter”; “the clearing was smaller than he remembered”; “it was darker and smaller than he remembered”; and yet “inside it hadn’t changed, and it made his chest tight to see”. This uncanniness, along with the strange sensation that the shack had been waiting for him, confers an expectant air of reckoning on the setting. Frank can’t bear to see the beds where he and his parents once slept, nor the wedding-cake figurines of his forebears, and sets about doing over the past as he works through his misery at losing Lucy. “The bloody feel of some bastard terrible thing swimming inside him” is one that won’t let up either for Frank or the reader. He soon gets a job dealing in freight and makes friends with neighbours Bob and Vicky, as well as Sal, their hot-headed daughter who turns up one day and suggests he employ her to work on his “farm”. Memories of Lucy haunt him while in the background the news of missing local girl Joyce Mackelly develops in poignant counterpoint.

In our parallel narrative, Leon’s father goes to fight in Korea. When he returns from the war he is a shadow, no longer capable of producing the beautiful cakes that made his immigrant family’s name in Australia. The bakery is left in Leon’s care, and he tends to it faithfully until the day of his conscription into another war. In Vietnam, his experiences are told, in a vein of dark humour, through cooking similes and metaphors: “the heat glazed him”; “inside [the jungle] their skin glowed white like they’d been rolled in caster sugar”; “mud coated his trousers hotly and stuck like burnt chocolate to his boots”. He learns to kill. In Saigon he buys a Zippo with the words “After the Earthquake, a Fire” inscribed on it. When he returns, he too is changed, unable to relate in quite the same way to the people he loves.

Wyld, who works (and writes) in a book shop in London, spent much of her childhood in Australia, and her familiarity with its other-worldly flora and fauna is a great asset. One particularly breathless sequence with a shark stands out; but there are countless creepy-crawlies throughout, and near-ubiquitous chickens. Wyld’s prose has a terse beauty, a leanness that often approaches poetry. Her imagery is exquisite, especially when it comes to the depiction of male emotion. Leon watches on as “the tears ran out of his father like a squeezed lemon”; we later see “the grotesque smile that was a man crying”. (She’s equally adept in a comic register, incidentally — I particularly loved Frank carrying his stove “like a man slow-dancing with an orang-utan”.)

After the Fire, a Still Small Voice is a spare epic. Of fathers and sons but, even more, of intergenerational failures of understanding. Its compactness gives it heft, its colloquial ease the clear peal of authenticity. Want to hear more? Here’s Evie Wyld in an interview with Granta Magazine, which last year named her one of their twenty Best Young British Novelists (a distinction previously conferred on Zadie Smith, Martin Amis, Alan Hollinghurst and Jeanette Winterson).

https://soundcloud.com/ted-hodgkinson-granta/evie-wyld-the-granta-podcast

You can buy After the Fire, a Still Small Voice at McNally Jackson here. Evie Wyld is a guest at our next Seriously Entertaining show, “In Case of Emergency”, on April 28. Buy tickets here and follow Wyld on Twitter here!