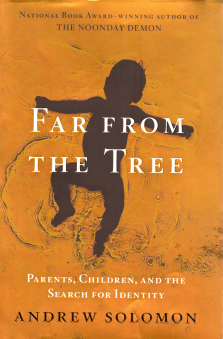

If, like me, you saw David Lynch’s Eraserhead at an impressionable age, or The Omen, or you read Lionel Shriver’s We Need To Talk About Kevin, the prospect of parenthood may be haunted by the fear that your progeny turn out in some way aberrant. Read Andrew Solomon‘s Far From the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity (Scribner Books, 2012), though, and you will be haunted much more by the word aberrant ever having crossed your mind. Through twelve chapters, Solomon investigates the experiences of parents and children living with deafness, dwarfism, transgenderism, criminality, prodigiousness, autism, schizophrenia, Down Syndrome, severe disability, or a history of rape. “This book’s conundrum,” Solomon writes in the introductory chapter, “is that most of the families described here have ended up grateful for experiences they would have done anything to avoid.” Far From the Tree, a book ten years in the writing, drawing on interviews with more than three hundred families, yielding forty thousand pages of transcripts, progresses steadily towards an understanding of that gratitude. In so doing, it’s a book that might actually change your life.

For the most part, Solomon investigates so-called “horizontal” (uninherited) identities. These may include differences of sexuality, physical or mental disability, psychopathy, genius, or autism. His own experience growing up gay informs his understanding of these terms, and he relates how the process of writing Far From the Tree has changed his views of his parents: “I wrongly felt the flaws in my parents’ acceptance as deficits in their love. Now, I think their primary experience was of having a child who spoke a language they’d never thought of studying.” Again and again, through the countless examples Solomon offers, we are led to see how even being prepared to learn that new language can be sufficient to ensure that your child is loved for who they are rather than who they might have been.

In many of the states of being Solomon investigates, the origin of difference is unclear. More than two hundred genetic conditions can lead to small stature. Autism is little more than “a catchall category for an unexplained constellation of symptoms.” Schizophrenia, likewise, has an undetermined genetic provenance, emerging as it does through a large variety of genotypes and phenotypes. Other conditions — including deafness and Down Syndrome — can be easier to follow through genetic lines and may be detectable before birth. In all cases, research is progressing apace to find origins, treatments, even cures. This can be positive: there’s no denying that the alleviation of certain conditions — especially in the case of those living with multiple severe disability — is a good thing for parents and their children. But as Solomon demonstrates, around many of these states of being have coalesced rich and proud cultures. The conflict between “illness” and “identity” is one of the major themes of his book.

In many of the states of being Solomon investigates, the origin of difference is unclear. More than two hundred genetic conditions can lead to small stature. Autism is little more than “a catchall category for an unexplained constellation of symptoms.” Schizophrenia, likewise, has an undetermined genetic provenance, emerging as it does through a large variety of genotypes and phenotypes. Other conditions — including deafness and Down Syndrome — can be easier to follow through genetic lines and may be detectable before birth. In all cases, research is progressing apace to find origins, treatments, even cures. This can be positive: there’s no denying that the alleviation of certain conditions — especially in the case of those living with multiple severe disability — is a good thing for parents and their children. But as Solomon demonstrates, around many of these states of being have coalesced rich and proud cultures. The conflict between “illness” and “identity” is one of the major themes of his book.

In many cases, the need for pride is a reaction to an ongoing history of oppression, misunderstanding, and abuse. The construction of an identity that redefines what has historically been seen as a deficiency often entails a reconceptualization of a state of being in positive terms. Some proponents of Deaf culture, for example, don’t look on deafness as a lack of hearing. Instead, they see in Sign language a beautiful, elegant, complete mode of expression; they consider deaf people to be disabled only if compromised by a system that enforces them into a state of unsatisfactory bilingualism, fluent in neither Sign nor spoken language. Cochlear implants, which in some cases can offer significant assistance to deaf people in getting by in the hearing world, are seen — at the extreme end — as instruments of genocide, a step on the road to eliminating Deaf culture in all its richness. Many little people (LPs) see extended limb-lengthening procedures in similar terms, and object to the notion that their condition requires correction.

Neurodiversity advocates worry that medicalizing autism considers the needs of parents more than children. One of Solomon’s interviewees, Ari Ne’eman, who has Asperger’s, complains a society that treats people as if they must all be measured against a bell curve values mediocrity above all else. At the extreme end of things is the Mad Pride movement, which advocates for the rights of schizophrenics:

These activists believe they are throwing off the yoke of oppression. They both have a serious mental illness and have suffered tyrannical subjugation; the question is whether they can address the subjugation without making false claims about the nature of mental health.

This is where identity politics gets foggy. As Solomon points out, if Deaf advocates claim deafness is not a disability, do deaf people still qualify for consideration under the Americans with Disabilities Act? Should the “stoic grace” exhibited by many schizophrenics be reconsidered as an element of a new, positively constructed identity? One can certainly treat identity with too much respect. In treating with children who identify as trans, for example, proceeding with hormone treatment or surgery at a young age could be extremely damaging in the long term.

Andrew Solomon

In the case of transgenderism, Solomon writes, “Received wisdom is evolving at a breakneck pace,” and the same could be said of many of the states of being described in Far From the Tree. We are privy to the struggles of countless parents as they try to introject changing social attitudes at the same time as realigning their hopes for their children with their uncommon circumstances. These are some of the most moving passages of the book. Some of the marriages Solomon encounters break down, unable to deal with the pressures of raising a child so dependent; others endure, strengthened by the shared challenges overcome or managed. One of Solomon’s most extraordinary encounters is with Sue and Tom Klebold, whose son Dylan was one half of the duo who planned and carried out the high-school shootings at Columbine in 1999. As Solomon points out, just as some families have to deal with the personality-altering emergence of autism or schizophrenia, so others must cope with the unexpected emergence of criminality or violence in the family. The Klebolds’ case is extreme and notorious, yet Sue is still able to say, by way of conclusion, “I know it would have been better for the world if Dylan had never been born. But I believe it would not have been better for me.”

The transfiguring power of parental love is clearly something to be celebrated, even in such extreme cases. Reading what Solomon calls his “how-to manual for receptivity,” one can only hope — should one seek to become a parent — that one might be so transfigured. The alternative is too appalling to countenance. The chapter on autism concludes with a litany of filicides, only just over half of which resulted in jail time for the perpetrators. Around fifty percent of the victims of rape in Iraq following military occupation a decade ago were murdered by their families, shamed by the prospect of children born out of rape. Even child prodigies, whom one might think to be all-round blessed, often find themselves the victims of extraordinary parental pressure or abuse, even if their fate is nowhere near as violent as others’.

There’s an incredible amount to take away, right to the final chapter on Solomon’s experience of becoming a father. It’s in many ways a humbling read, a reminder of the extraordinary power and reach of love, as well as a dismantling of concepts you might have assumed to be gospel. Even the very first sentence, “There is no such thing as reproduction,” is a challenge. But if one follows through on Solomon’s reasoning, here and throughout, one sees the wisdom in shedding preconceptions and returning to first principles: “we must love [our children] for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do. Loving our own children is an exercise for the imagination.”

Far From the Tree will help expand that imagination.

You can buy Far From the Tree at McNally Jackson and follow Andrew Solomon on Twitter. Buy tickets for our Seriously Entertaining show Inside the Lie on September 29 at City Winery, featuring Solomon, Natalie Haynes, John Guare, Gail Sheehy, Marcelo Gleiser, and Gary Shteyngart, here.