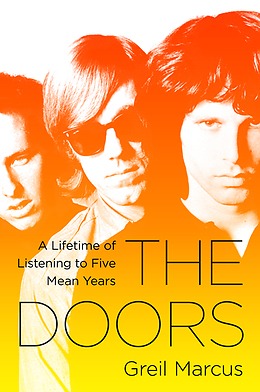

The Doors: John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison

When I was seventeen I went through a massive Doors phase. I loved the music, of course. But no doubt it was also partly an attraction to the grotesque, doomy romanticism of Jim Morrison, “his ideal of following in the footsteps of Rimbaud replaced by an image of Marat dead in his bathtub”. About a year ago I went through a second, more intense Doors phase. (Still there, actually.) And judging from the experience of Greil Marcus, just quoted, whose excellent book on the Doors is subtitled A Lifetime Listening to Five Mean Years (PublicAffairs, 2011), I’m going to spend the rest of my life returning to them again and again and again and…

Jim Morrison’s shamanic aura is at the heart of the Doors’ music. The band made an indelible mark on late ’60s US culture with their six top ten studio albums; astonishing, meandering live shows; and the notoriety occasioned by Morrison’s infamous exposure onstage in Miami in 1969. They even appear in a short vignette in Joan Didion’s kaleidoscopic essay “The White Album“, a literary affirmation of their cultural centrality. But what sustains the myth of the Doors is their eerie prescience, the spooky sensation that in their music lies an intuition of the darkness to come: the madness in Vietnam, the Manson Family murders, political assassination, Morrison’s own early death. As Marcus suggests,

After Charles Manson, people could look back at “The End,” “Strange Days,” “People Are Strange,” and “End of the Night” and hear what Manson had done as if it had yet to happen, as if they should have known, as if, in the deep textures of the music, they had. […] In the summer of 1969, people listened again to their Doors albums and said, Yes, it was all there.

“The End”, if one can hear it again afresh outside the opening of Apocalypse Now, is an extraordinary, violent, Oedipal saga.

http://youtu.be/4naoVjdFxCA

For Marcus, it’s a song that “feels as if it’s about to tear itself to pieces”, complete with a central section that recalls the murder of the Clutter family (as sensationalised by Truman Capote in In Cold Blood). He devotes a short chapter to listening to the song, recording his sensations:

Robby Krieger developed a way of saying, in a very few, quiet, spaced notes on his guitar, that something was about to happen. He could make you draw your breath […] Ray Manzarek shifts quietly behind him, a green river in the cave of the song […] there’s no sense of time passing […] Morrison’s words have the feel of phrases made up on the spot to fit or break the rhythms taking shape around him: the languid, sleepy “The west, is the best” followed by the staccato jump in the way the last five words of “Get here — and we’ll do the rest” pull the first two words after them like a weight pulling a house off a cliff […] the performance is a dance around a fire, with the pace determined by the flickers, which can’t be anticipated, that are never the same […]

Before I continue, an apology: clipping like this does a severe injustice to Marcus’s marvellously lucid prose, like skipping through a track on your iPod. He writes about music at the same pitch at which it’s heard, making it possible almost to re-experience the Doors’ music as you read about it. His imagination gives birth to images that recall and perhaps even enhance the experience of the music, as in his brilliant description of “L.A. Woman” as “Blade Runner starring Charles Bukowski instead of Harrison Ford”, or the moment in “The Crystal Ship” when Morrison finally raises his voice: “near the end, when he sings the title of the song as if he’s just discovered it: the three words, the perfect metaphor, the Flying Dutchman of the heart”. The thrill of reading Greil Marcus is the thrill of recognising one’s own hazy perceptions perfectly distilled into words.

Before I continue, an apology: clipping like this does a severe injustice to Marcus’s marvellously lucid prose, like skipping through a track on your iPod. He writes about music at the same pitch at which it’s heard, making it possible almost to re-experience the Doors’ music as you read about it. His imagination gives birth to images that recall and perhaps even enhance the experience of the music, as in his brilliant description of “L.A. Woman” as “Blade Runner starring Charles Bukowski instead of Harrison Ford”, or the moment in “The Crystal Ship” when Morrison finally raises his voice: “near the end, when he sings the title of the song as if he’s just discovered it: the three words, the perfect metaphor, the Flying Dutchman of the heart”. The thrill of reading Greil Marcus is the thrill of recognising one’s own hazy perceptions perfectly distilled into words.

In some ways it’s an exercise in extended metaphor. In Manzarek’s playing, “you can hear memories of late-night TV creep-show movie marathons”. In the opening seconds of “End of the Night”, you hear “a descending crescendo from Robby Krieger that turns off the lights [and] an answering three lines from Ray Manzarek that says he was waiting for this all along”. In “L.A. Woman”:

Jim Morrison is in the back of the sound, as if trailing the band on the street, shouting that he’s got this song for them, a new-type song, for a dime, it’d be perfect, and you can see the Morrison who’s singing, a man who in 1970 did look like a bum, a huge and tangled beard, a gut hanging over his belt, his clothes stained […] he can see the fear the Manson gang left in the eyes of the people he passes even as they avert their eyes from his, but he’s not afraid, and he knows he’s not the killer they’re afraid of.

Marcus uses the Doors’ lyrics, his own imagery, and a wealth of references — Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, Elvis, Oliver Stone’s biopic of the band (which he passionately defends), youth exploitation movies — to evoke in words the inexpressible: the music’s rasa, its affect. His book is a kind of poetics of the Doors.

Marcus is clearly not a superfan. He describes Waiting for the Sun as “the band’s floppy third album” and later big-time hates on The Soft Parade, saying of its opening track, “Morrison sounded as if he had a bag over his face, so no one would know who was singing it”. But this has the perverse rhetorical effect of strengthening his overall thesis, fortifying it against criticism by preemptively discarding the “Hello, I Love You”s of the catalogue. When they were good, though, they were very: the Doors, in moments of pure alchemy, produced “the sound of the times that no one else made”. Hear, hear. And listen again.

You can read Greil Marcus’s Rolling Stone pieces going back to 1968 here and buy The Doors: A Lifetime of Listening to Five Mean Years at McNally Jackson here.