The story begins in media res. The Midterms, 2010: in something of a rout, the Republican Party captures sixty-three seats in the House of Representatives, the largest number to change hands since 1948. What honeymoon there might have been for America’s forty-fourth president is definitively over. The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies, published in paperback by Simon & Schuster this week, picks up the national narrative from here and takes it through to the presidential election of 2012. Jonathan Alter, its author, has covered nine presidential elections and considers 2012 to be “a hinge of history”, “a titanic ideological struggle over the way Americans see themselves and their obligations to one another” in which the battles fought go back “to the dawn of the republic”. Hefty language requires ample support, and Alter’s the writer for the job: The Center Holds is a fantastically detailed account of the 2012 presidential election. Drawing on meticulous research and interviews with more than two hundred people close to the Obama and Romney campaigns, it comes to read almost like a handbook on how (not) to win an election. One by one, Alter ticks off all the major factors that contributed to the eventual outcome while simultaneously driving the story forward like a thriller.

The story begins in media res. The Midterms, 2010: in something of a rout, the Republican Party captures sixty-three seats in the House of Representatives, the largest number to change hands since 1948. What honeymoon there might have been for America’s forty-fourth president is definitively over. The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies, published in paperback by Simon & Schuster this week, picks up the national narrative from here and takes it through to the presidential election of 2012. Jonathan Alter, its author, has covered nine presidential elections and considers 2012 to be “a hinge of history”, “a titanic ideological struggle over the way Americans see themselves and their obligations to one another” in which the battles fought go back “to the dawn of the republic”. Hefty language requires ample support, and Alter’s the writer for the job: The Center Holds is a fantastically detailed account of the 2012 presidential election. Drawing on meticulous research and interviews with more than two hundred people close to the Obama and Romney campaigns, it comes to read almost like a handbook on how (not) to win an election. One by one, Alter ticks off all the major factors that contributed to the eventual outcome while simultaneously driving the story forward like a thriller.

Partisanship. “It was Obama’s historical misfortune to serve as president during the most partisan era in modern American history,” says Alter. On the night of his first inauguration, “GOP public opinion impresario” Frank Luntz hosted a dinner for Republican lawmakers at which it was decided that the party must unite in its opposition to the president and everything he proposed. As legislative gridlock became a hallmark of the first term, it seemed this plan had become pretty much gospel for the GOP. Alongside what was happening at Congressional level, Alter charts the rise of Grover Norquist and the Tea Party, and speculates on the effect of the right-wing media, exemplified by Fox News and Rush Limbaugh. At the fringes lies “Obama Derangement Syndrome”, a phenomenon Alter characterises as racist at heart, which finds its most prevalent myth in the birther movement and its most prominent figurehead in Donald Trump. That Obama was able to overcome all of these things to win a second term may yet fundamentally change the terms of the debate.

Author Jonathan Alter

The “Moneyball” effect. In Alter’s terms, 2012 was Chicago v Boston, sub-characterised as Silicon Valley v Mad Men. “The Floor” in Obama HQ “was full of young, supersmart Obamaniacs, who often sat on large rubber balls for chairs, played Ping-Pong on breaks, and rang a bell every time the campaign raised a million dollars”. Many of the campaign team were veterans of 2008 and knew that to win again required a whole different game plan. Their harnessing of Big Data, which allowed them to microtarget the electorate, proved critical to mobilising the 900,000 volunteers the Democrats had behind them by election day. Boston, on the other hand, suffered from a “geek gap”, their team instead comprising old-school advertising muscle — including a veteran of Reagan ’84, an election that took place before some of Obama’s campaign managers were even born. Despite aspirations of big-data savviness, Romney’s campaign had neither the time nor the funds to invest in analytics in a meaningful way. Its most ambitious technological development, ORCA, which was supposed to ensure that missing Republican voters were targeted on election day for their last-minute votes, ended up dead in the water, leaving the candidate himself to rely on TV news. Broadband trounces dial-up.

Demography. Reagan rode to a landslide victory in 1980 on the same proportion of the white vote McCain won in his failed 2008 bid. In the twenty years between 1992 and 2012, the proportion of non-white voters increased 16 percent. The redistricting that took place in newly Republican state legislatures after 2010 and the laws restricting voting passed in nineteen states between then and mid-2012 certainly had a huge effect on the election. But they were not enough to overpower the support Obama had from the African-American and Latino population. In some all-black precincts in Philadelphia, Mitt Romney failed to pick up a single vote, and Chicago ran nearly four times as many Spanish-language TV spots as Boston. Race was not the only factor, though. The president’s evolved position on marriage equality won him the lion’s share of the LGBT vote, while repeated gaffes on the subject of gender equality from Republican candidates (most notoriously, Todd Akin’s talk of “legitimate rape”) near-guaranteed Obama a strong showing from female voters.

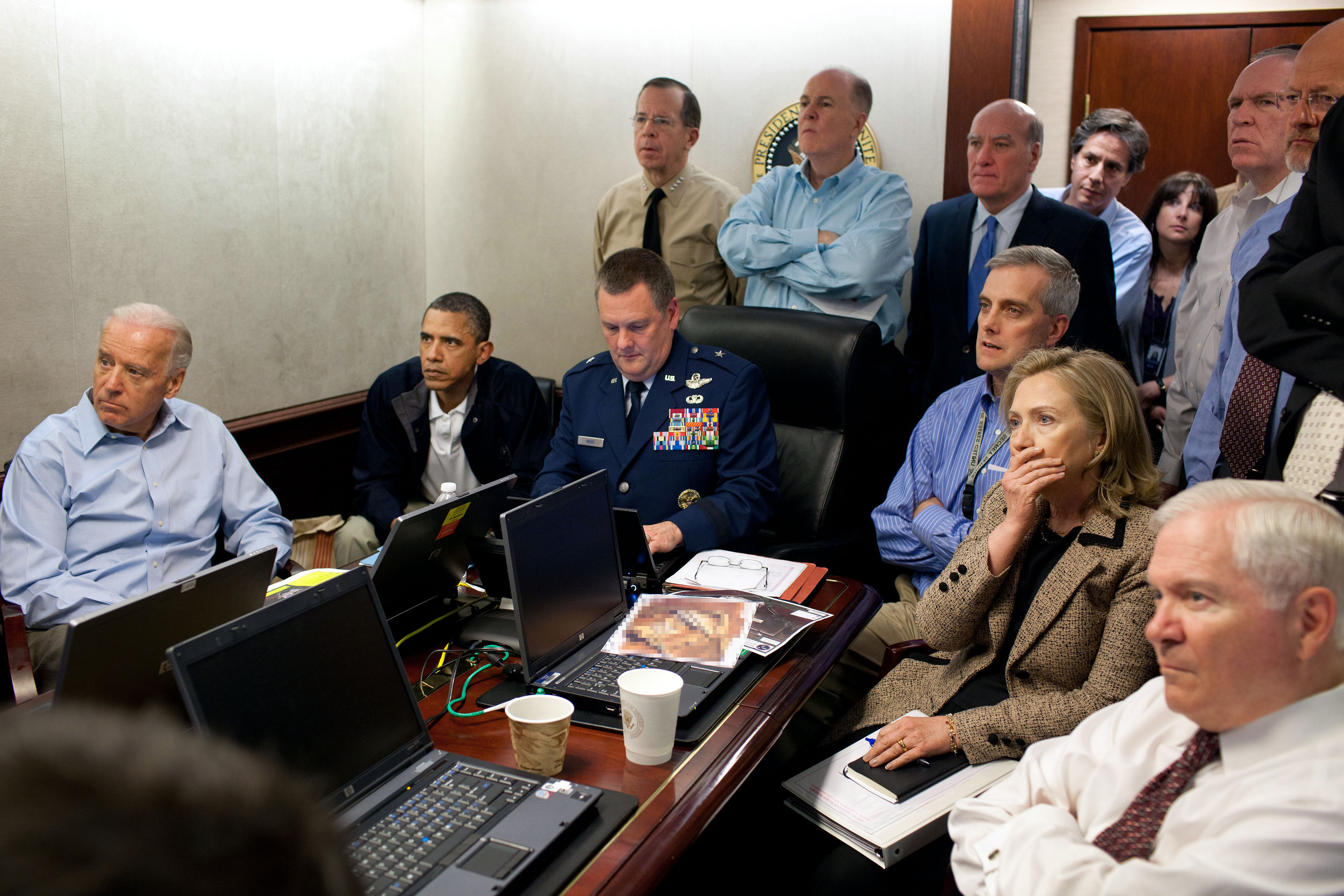

Vice President Joe Biden, President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, amongst others, in the Situation Room in the White House monitoring the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, May 2011. Photo by White House photographer Pete Souza.

History. One of the most dramatic chapters in the book details the killing of Osama bin Laden, which Alter believes history will see as one of Obama’s signature acts. Bin Laden’s vanquishing, and the deaths of many other senior al-Qaeda officers during the first term, put paid to a common impression of Democratic military weakness, while stories of Obama’s decisiveness despite the doubts of others contributed to perceptions of him as a strong leader. But the discovery of America’s Most Wanted was not the only time history would change the direction of the debate. In October 2012, eight days before the election, Hurricane Sandy made catastrophic landfall in New Jersey. The president’s swift action and warm bipartisan relationship with Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey marked for some — President Clinton allegedly among them — the turning-point of the election.

All this having been said, The Center Holds is also vocal on what Alter perceives to be Obama’s weaknesses, including his failures as a communicator and his lacking “the schmooze gene”. And at many points in the story, he suggests how things might have taken a different turn. Obama’s disastrous debate performance in Denver, Alter writes, was a moment when he “almost threw his presidency away”. And would Romney have had a stronger showing without the release of the notorious “47 percent” incident? What was the effect of the attacks on the consulate buildings in Benghazi? Or indeed Clint Eastwood?

It’s all academic, of course. At the end of the whole extraordinary process, it turned out that all that had happened could be summarised in three words and an image redolent of the sort of blue-sky optimism that had propelled Obama to the White House in 2008. Even knowing the ending, in Alter’s hands it’s a thrilling ride.

Four more years. pic.twitter.com/bAJE6Vom

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) November 7, 2012

Jonathan Alter, who you can follow on Twitter here, is a guest at our next Seriously Entertaining show, The Ink Runs Dry, on May 20. Tickets are on sale here.