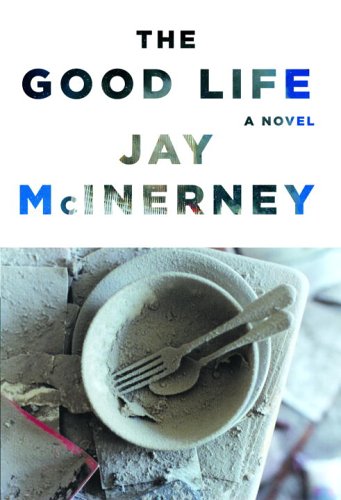

In a 2005 article for the Guardian entitled “The uses of invention”, Jay McInerney set out to counter the prevalent concern that literature was no longer up to the task, following 9/11, of processing world events. His contribution to the proof was The Good Life (2006), a novel set in the autumn of 2001 in the bedrooms of wealthy Manhattanites dealing with the aftermath of the destruction downtown. It was McInerney’s seventh novel and a sequel of sorts to 1992’s Brightness Falls.

In a 2005 article for the Guardian entitled “The uses of invention”, Jay McInerney set out to counter the prevalent concern that literature was no longer up to the task, following 9/11, of processing world events. His contribution to the proof was The Good Life (2006), a novel set in the autumn of 2001 in the bedrooms of wealthy Manhattanites dealing with the aftermath of the destruction downtown. It was McInerney’s seventh novel and a sequel of sorts to 1992’s Brightness Falls.

The book’s central insight is given to Luke McGavock around halfway through: “Personally is maybe the only perspective we have.” Like much of the fiction published since 9/11, McInerney’s novel is not principally about terrorism or the fall of the World Trade Center. Instead, it examines the effects of the attacks on individuals. His characters’ lives are all balanced somewhat precariously before September 11; the subject of the book becomes how such an epochal event can change perspectives in unforeseeable ways.

Luke is something of an avatar for McInerney, who also spent the weeks following 9/11 working in a soup kitchen downtown, and he is occasionally blessed with an almost authorial clairvoyance. At a benefit at Central Park Zoo:

The women were beautiful in their gowns, or at least glamorous in their beautiful gowns, their escorts rich in this richest of all cities, and Luke had never felt less like one of them, reminded now of the figures he’d seen this summer in Pompeii and Herculaneum, frozen in their postures of feasting and revelry.

Meanwhile in TriBeCa, Russell and Corrine Calloway are thrown out of joint by the sudden arrival of Corrine’s flighty sister, Hilary, who is the biological mother of their twins. Russell has been having an on-off affair with his assistant, and that secret has already soured the milk in their marriage, even if Corrine doesn’t know why. The couples are loosely linked by mutual friends, but it’s the impending catastrophe that causes their orbits to collide.

Luke narrowly misses being directly caught up in the attacks and spends September 11, as the financial district is engulfed in ash and debris, searching for his friend Guillermo, whom he was supposed to meet in the Windows on the World that morning. The following day as he stumbles home, he meets Corrine, who is moved by events to volunteer for the rescue-and-relief effort. She gives him her number and asks him to call when he gets home. What starts off as a warm friendship at the soup kitchen at which they both volunteer swiftly becomes passionate and romantic.

Luke narrowly misses being directly caught up in the attacks and spends September 11, as the financial district is engulfed in ash and debris, searching for his friend Guillermo, whom he was supposed to meet in the Windows on the World that morning. The following day as he stumbles home, he meets Corrine, who is moved by events to volunteer for the rescue-and-relief effort. She gives him her number and asks him to call when he gets home. What starts off as a warm friendship at the soup kitchen at which they both volunteer swiftly becomes passionate and romantic.

“Staggering up West Broadway, coated head to foot in dun ash, [Luke] looked like a statue commemorating some ancient victory, or, more likely, some noble defeat — a Confederate general, perhaps.” The Civil War reference, like the earlier nod to Pompeii and Herculaneum, nudges the reader towards understanding the events of 9/11 in a broader historical context. It transpires that Luke’s great-great-grandmother had nearly fifteen hundred Confederate soldiers buried in the family cemetery during the Civil War and that she spent the months following their deaths writing to their mothers. McInerney seems to be suggesting that it is in this way, through personal connection, that national tragedy might be worked through.

“New York doesn’t have a collective memory,” Luke claims later, an assertion partially verified by the novel’s action. When he first returns home, for instance, Luke’s wife, Sasha — whom he suspects is having an affair with one of the billionaires on their benefit circuit — exhibits emotions he assumed she was no longer capable of. Ultimately, though, the “pathways of intimacy” between them were “stopped up with the debris of old resentments, which these catastrophic events had failed to dislodge”. What transforms the lives of McInerney’s characters, and drives the action of the novel, is not the fall of the towers but the interpersonal unpleasantness occasioned by stale marriages and unmet desires.

But there is an affective transformation. For Russell, the “towers of midtown” become “a dozen vertical targets in the sky”. Corrine, thinking of her children’s wellbeing, concedes that “she would never know the untroubled sleep of youth, that she would always be hovering near the surface of consciousness in the perpetual light of the restless city, alert to the sound of a cough, the thump of a falling body, the drone of a plane overhead.” It’s this newfound appreciation of the unbearable lightness of being that brings about change in The Good Life. The frantic couplings in the aftermath of the attacks, a hallmark of life in wartime, are merely an extension of the mostly submerged awareness that life is short and if you blink you’ll miss it. Luke, towards the end of the novel, approaching Manhattan by road, finds that “even the absence of the twin monoliths, and the ghostly smudge over the tip of the island, seemed inextricably linked in his mind with Corrine.” The capacity for figurative thought — however narcissistic, obscene, or deplorable in this case — is nonetheless profoundly human.

As McInerney states in the Guardian piece, Norman Mailer advised him to wait ten years before trying to tackle 9/11 in fiction. And there’s no doubt McInerney would write a different novel now. But what Mailer perhaps neglects is the value of novels like The Good Life, or Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2004), or Don DeLillo’s Falling Man (2007), or, more recently, Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge (2013). None of these attempts to swallow whole or process entirely the extraordinary largeness of 9/11. The process of recovery is gradual, and perhaps the only perspective that can be taken, at the very least in the short term, really is the personal.

In an interview with the Daily Beast last year, McInerney confirmed that he is working on the conclusion of an informal trilogy begun with Brightness Falls and continued with The Good Life. In the same way that all such sagas add cumulatively to our understanding of history as it is lived by its characters, perhaps this final volume will add another perspective to the mosaic.

You can buy tickets for the House of SpeakEasy’s March 18 show, “Are You For Sale?”, featuring Jay McInerney, here.