Scheherazade.2 — Dramatic Symphony for Violin and Orchestra (2014)

by John Adams

New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall; conducted by Alan Gilbert; soloist Leila Josefowicz

World premiere: Thursday, March 26, 2015

Insights at the Atrium — Artist and Muse: John Adams and Leila Josefowicz

David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center

Monday, March 23, 2015

John Adams isn’t sure if his latest composition can be played by a man. Scheherazade.2, described as a “dramatic symphony for violin and orchestra,” emerged from a collaboration with the violinist Leila Josefowicz, and after seeing her play it, it’s certainly difficult to imagine the same work essayed by a male soloist. In a talk ahead of the world premiere, Carol Oja, the New York Philharmonic’s Leonard Bernstein Scholar-in-Residence, suggested to Adams that he had written “a feminist concerto.” And while he confessed that he never had a coherent “libretto” for the piece in his head, he did concede that she’s “like Isolde or Elektra. I can’t think of a concerto that’s that dramatically specific.” (To note, he rejects “concerto,” preferring the Berliozian construction “dramatic symphony”.) In Scheherazade.2, the line between actor and violinist blurs. To perform it, Josefowicz prepared much as an opera singer would. She memorized the work, internalized it, began thinking of it as theater. “There’s this idea, this feeling, these gestures,” she said; “how do I make this as strong as possible through vibrations on a violin?”

On the evening of the talk, three nights before the premiere, Josefowicz joined pianist John Novacek for a recital of Adams’s 1995 work Road Movies at the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center. “Being on the road is an American tradition,” Adams observed afterward; “a sort of mythic-imaginative experience for Americans.” The music of Road Movies reflects this Americanness in its swing, its syncopation, its minimalism. It is very much at the American-vernacular end of the spectrum of Adams’s work, and Josefowicz was well suited to it. Strutting like Mick Jagger; ripping into her violin with such violence that several bow-strings were left waving through the air in her wake; her face screwed up in rude defiance of the fiendish intricacy of Adams’s dazzling (re)iterations. To see her up close on Monday was to receive a special preview of her Thursday-night masterclass, which’d be seen by most from a much greater distance.

Come Thursday, one had to wait till the second half of the Philharmonic’s program to hear Josefowicz let loose. But the first half did offer intriguing whispers of what would follow. Anatoly Lyadov’s miniature The Enchanted Lake (1909) emerged shimmering from the fog of the softest bass drum rumble you ever heard. Later, the harp and celeste added an exotic twist to an exquisitely delicate performance. At its conclusion, conductor Alan Gilbert, sorcerer-like, held the spell an extra few seconds as Avery Fisher experienced a rare complete silence. Following up the Lyadov, the inclusion of Stravinksy’s Petrushka (1911), first performed by the Ballets Russes, was of double significance. Even without dancers it tells a story vividly through music, as Adams’s new work would half an hour later. But also, among the images of Scheherazade that inspired Adams was a design of Sergei Diaghilev’s for a production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, staged only a year prior to Petrushka.

In his program note, Adams wrote:

The impetus for the piece was an exhibition at the Institute du Monde Arabe in Paris detailing the history of the Arabian Nights and of Scheherazade and how this story has evolved over the centuries. The casual brutality towards women that lies at the base of many of these tales prodded me to think about the many images of women oppressed or abused or violated that we see today in the news on a daily basis. In the old tale Scheherazade is the lucky one who, through her endless inventiveness, is able to save her life. But there is not much to celebrate here when one thinks that she is spared simply because of her cleverness and ability to keep on entertaining her warped, murderous husband.

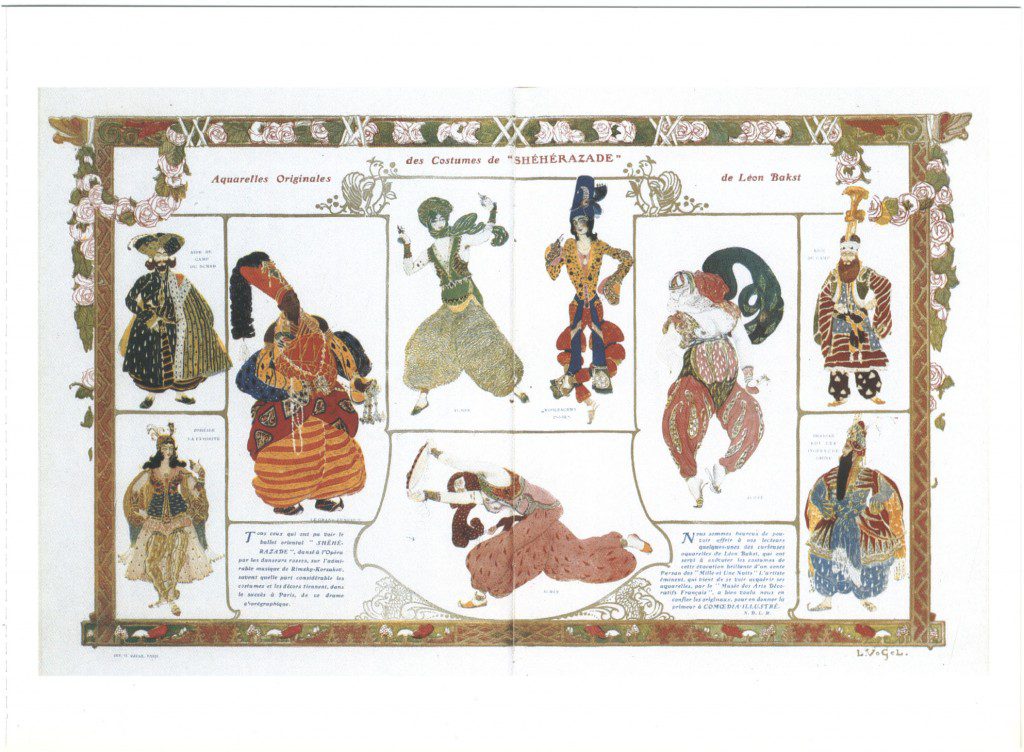

Léon Bakst’s costume designs for Diaghilev’s production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade.

Adams’s piece is a little more abstract than Rimsky-Korsakov’s, although, as he pointed out on Monday, it shares a certain (large) scale and the use of the violin to denote a principal female voice. Its four movements tell a loose story. In the first, a “Wise Young Woman” is pursued “by the True Believers.” In the second, we see this woman in love — perhaps, Adams suggests, with another woman. The third movement, the most intense, concerns “Scheherazade and the Men with Beards” and depicts a trial scene at the end of which our heroine is condemned. “Escape, Flight, Sanctuary” is the title of the work’s ambiguous final movement.

“I’m not really good at chamber music,” Adams confessed on Monday. “It takes me twenty or thirty minutes to get my jumbo off the runway.” This wasn’t a problem in Scheherazade.2, which launched with an orchestral flourish and the immediate dramatic entrance of the cimbalom, an instrument Adams used to similar alien effect in The Gospel According to the Other Mary (2012). Unlike that previous work, Scheherazade.2 is unstaged. But there was a sense, in Josefowicz’s choice of clothing, of a conscious theatricalism: the rich, autumnal coloring of her harem pants and loose tunic, in concert with her short, asymmetric haircut, stood in dramatic contrast to the penguin monochrome of the rest of the Philharmonic. This fit the “character” she was playing, a persecuted individualist getting by on her wits. Adams has described the relationship between violin and orchestra as “a David-and-Goliath scenario;” this was very visibly the case on Thursday night.

Theater’s not a bad way to understand the piece. At times, the movement of the violins behind Josefowicz (almost all women, I noticed) matched hers; their unified bowing was an image of visceral sympathy. At others, she and the rest of the strings conversed in a sort of syncopated stichomythia; it was at these times when her character’s forcefulness was most evident. In the third movement, when Scheherazade is on trial, Alan Gilbert became almost magistrate-like, forced to mediate between the rational lyricism of Josefowicz and the terrifying irruptions of discordant brass off to his right. “It’s the most visceral movement,” Josefowicz said on Monday. “In terms of storyline, this is the most real. I think you will know when she is condemned.” There was a visual cue, in fact. In a brief pause from her playing, as judgment was passed in the brass section, Josefowicz raised her eyes to the ceiling of Avery Fisher Hall, as if looking up from the bottom of a deep well. When she took up her bow again, there was a shocking new timbre in her playing, a sound stripped entirely of the warmth and the spirit we’d heard just minutes before.

Adams is unafraid of politics. The Gospel According to the Other Mary linked the story of Jesus Christ to the labor activism of César Chávez. His operas Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic all took controversial twentieth-century events as their subject. Both on Monday and in a brief interview with Gilbert before the performance on Thursday, Adams suggested that the “Men with Beards” in Scheherazade.2 could represent Rush Limbaugh just as easily as the Taliban. Though no doubt spoken as a humorous provocation in the liberal surroundings of Lincoln Center, this deliberate lack of specificity, Adams’s positioning of the work as pure metaphor, awaiting interpretation, encourages the viewer-listener to see in Josefowicz/Scheherazade the plight and the suffering of women in multiple contexts around the world.

But it’s far from being a passion play. Our violinist-heroine is defiant, fierce, powerful. As Josefowicz put it on Monday, “She loves, she struggles, she fights, she embraces, she gets above the fray, she gets in the thick of it.” “She works out!” Adams added. It’s a dazzling portrait of virtuosic femininity. And in Josefowicz, Adams has found a perfect muse. “I know Leila,” he said. “I know how she plays. I know that crazy look when she’s out there rocking… She’s like a racehorse way ahead of the others.” The feeling is mutual; she commissioned the production of an electric violin especially to perform Adams’s The Dharma at Big Sur. “So I felt like I owed her her own piece!” Adams quipped. But when Oja asked him what in particular inspires him, he sighed. “Words fail. That’s why I’m a composer! … She’s just utterly fearless.”