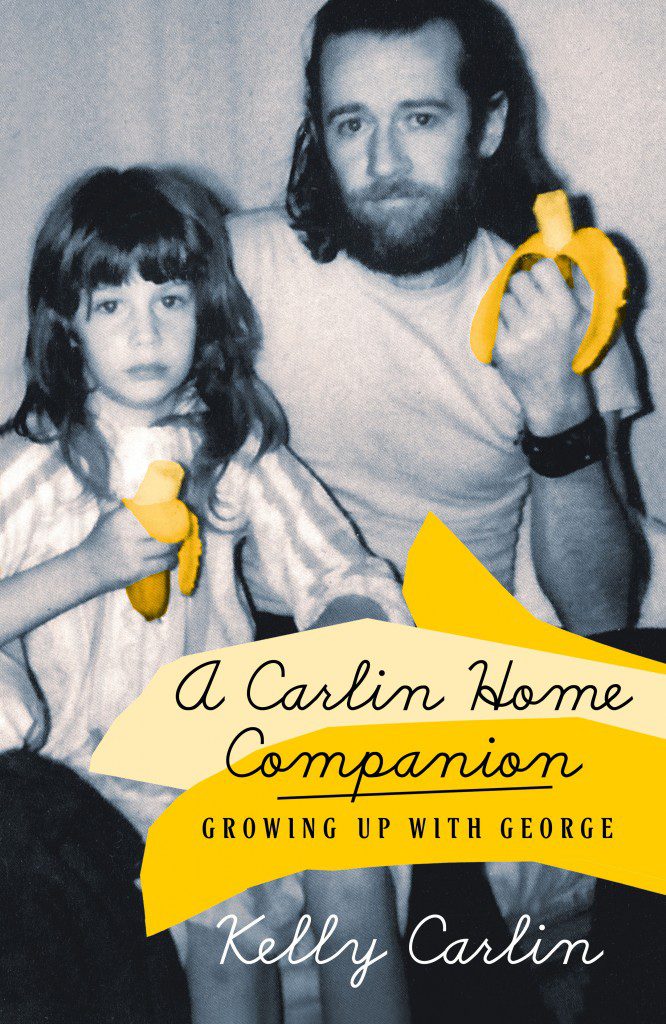

A Carlin Home Companion: Growing Up With George

A Carlin Home Companion: Growing Up With George

by Kelly Carlin

St. Martin’s Press, 2015; 336pp

George Carlin plays the part of the magical storybook father for much of his daughter Kelly’s new memoir, A Carlin Home Companion, due to be published on September 15. He’s the fun dad, the dad who lets you do as you please. He mails cryptic postcards to Kelly with single words on, for her to string together as sentences; he makes peanut-butter sandwiches for her when she doesn’t fancy her mother’s cooking; and when he bakes with her, he makes one batch of “Kelly’s Spice Cake” and one of George’s (“another box of cake mix and a Baggie of weed”).

The first third of this warm, witty, and ultimately wise book tells the story of George and Brenda, Kelly’s mother, up to the late 70s. Born in New York and inspired by comedians he saw at the movies, George early on hatched what Kelly refers to as the “Danny Kaye plan”: to become an entertainer. “There was never a plan B.” On the road, building his career as a stand-up, he met Brenda Hosbrook in Ohio in 1960. What, he asked her, does one do in Dayton after a show? “Well,” she replied, “you could find a diner and have some breakfast, or… Or you could find a girl with a stereo hi-fi and go home with her.” Politely taking the hint, he leaned in: “Do you have a stereo hi-fi?” They were married soon after, and in 1963 Kelly was born. George’s career steadily improved, and by the end of the 1960s, thanks to the popularity of his many skits, including the Hippie-Dippie Weatherman and the Indian Sergeant, plus his success on The Tonight Show, the Carlins were living in Los Angeles and the cash was flowing. So, unfortunately, was the booze. And the cocaine.

George would go on, of course, to become one of the most significant comics of the American century. After Carlin died, in 2008, Larry King devoted an entire show to him as a tribute. Jerry Seinfeld, writing in The New York Times, declared that “his brilliance fathered dozens of great comedians.” Kelly received heartbroken tributes from Jon Stewart, Lewis Black, and Garry Shandling. People still know, and recite, the seven words you can never say on television, while the view counts on pirated YouTube clips of Carlin’s fourteen HBO specials (recorded between 1977 and 2008) rank in the millions. One generation knew him first as Rufus in the Bill and Ted movies, and rediscovered him watching the HBO shows. A younger generation know his voice from Pixar’s Cars and have yet to discover the delights of his views on bullshit, suicide bombers, the fate of the planet and so on. He was a true original, an iconoclast, a humanist. Even in the 60s, Kelly writes, “On the outside my dad may have looked like the man his mother wanted him to be, with his clean-cut face and sharkskin suits, but inside he was a pot-smoking radical just itching to tell ‘the man’ to go fuck himself.”

But, as she later observes, on witnessing her father on a bad acid trip, “It seemed that becoming a counterculture god to the youth of America was not as easy as it looked.”

The early chapters are told with such fondness and love that it’s easy to believe that Kelly had a happy-go-lucky childhood. But despite her breezy tone (she describes herself at one point as the “addict whisperer”), the reality seemed to be that neither of her parents was ever fully sober for long periods during the 60s and 70s. Kelly was caught in the middle:

I tried to protect my dad from my mom’s alcohol-fueled irrationality by defending his behavior, and I’d protect my mom from my dad’s cocaine-fueled volatility, and at times violence, by trying to calm him down. When that didn’t work, I called their therapist, Al Weinstein. He’d try to scare some reason into both of them. He’d remind them that they were not only damaging themselves with all the drugs and chaos, but they were damaging me, too.

Again and again, though, in spite of all the fighting, the three of them would reaffirm their “Three Musketeers” status. And it’s hard to argue that the Carlins’ freewheeling solution to their problems — a family trip to Hawaii — was a lot more fun than family counselling. And these little patch-ups kept coming. As she became a teenager, Kelly still found almost all her requests being granted: horses, cars, marijuana… “Dad,” she’d ask, “can I have a hundred bucks to go buy some weed?” “Yes, of course,” he’d reply. “But don’t forget — when you get home leave me a few joints in my office.”

Kelly’s equanimity — and the generosity in her writing — stem from a seemingly boundless empathy for her parents. What they went through, we learn, she went through; first as a child, then as an adult. Brenda had married another young man before George when she got pregnant by him; so Kelly would have her own romantic missteps, including a stormy relationship with a man she came to fear so much that she slept with a gun under her pillow after she left him. George took so many drugs that he once woke up his young daughter terrified that the sun had exploded and they had just minutes to live; Kelly took so many drugs that she forgot she’d seen Yes in concert.

Kelly’s equanimity — and the generosity in her writing — stem from a seemingly boundless empathy for her parents. What they went through, we learn, she went through; first as a child, then as an adult. Brenda had married another young man before George when she got pregnant by him; so Kelly would have her own romantic missteps, including a stormy relationship with a man she came to fear so much that she slept with a gun under her pillow after she left him. George took so many drugs that he once woke up his young daughter terrified that the sun had exploded and they had just minutes to live; Kelly took so many drugs that she forgot she’d seen Yes in concert.

She has, it seems, come to understand them through the process of living her own life, much as (I suppose) we all do. Through meditation, her writing and her training in psychotherapy, she has learned — in Joseph Campbell’s words — to “participate joyfully in the sorrows of the world”. At one point, she confesses that she’s sad that her father never saw Driven to Distraction, the one-woman show she wrote about her childhood, “because by the end of each performance, the audience loved him even more than they had before.” It’s pretty much guaranteed that you’ll leave A Carlin Home Companion feeling the same.

Listen to Kelly reading an excerpt from A Carlin Home Companion here:

Kelly Carlin will appear at our next Seriously Entertaining show on September 22, 2015, at City Winery NYC. You can buy tickets here.

Follow Kelly on Twitter: