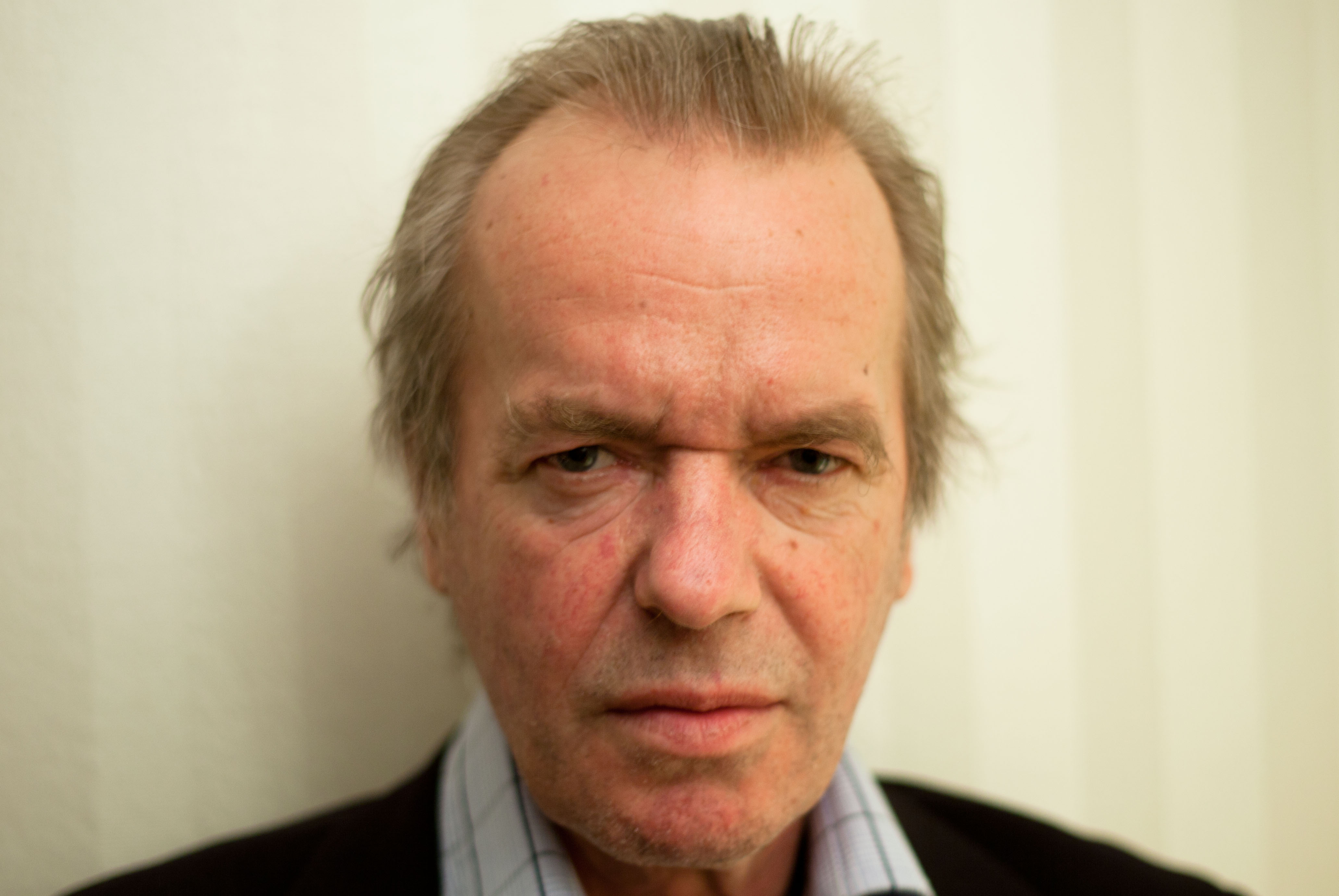

Martin Amis, photographed by Maximilian Schönherr in a hotel suite in Cologne, Germany, in 2012

Martin Amis was doubled on Saturday night at the New School. He was appearing as part of the tenth annual PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature, established by his great friend Salman Rushdie, who had a front-row seat for the occasion. Stage left was the real Amis, head cocked and battle-ready; opposite him sat interviewer and critic John Freeman; and between them was actor Anatol Yusef, who spoke only the historical Amis’s words, taken from interviews conducted since the 1970s in Interview magazine. The concept was simple but rather brilliant: Freeman would interview Amis-past and -present interactively, with Amis-present annotating, approving or contradicting his earlier selves. It was fascinating to watch.

Starting with The Rachel Papers (1973), Amis’s writing was inevitably compared with that of his father, Kingsley, whose most famous books include comic classic Lucky Jim and The Old Devils, winner of the 1986 Booker Prize. “I still think it delegitimises me in a weird way, having a writer-father,” said Amis-present, who’s written thirteen novels, several collections of short fiction and a wealth of criticism and social commentary. “I’m like Prince Charles, who talks with this sort of ex cathedra authority based on absolutely nothing at all. With me, everyone slightly suspects I got where I am through nepotism.” Now sixty-four, Amis has children of his own, but he was resistant to the idea that the family might automatically produce a third-generation writer. “It’s a very complicated thing, to encourage a child to follow your profession,” he said. Meditating on music and art, where dynasties of talent are much more common, he concluded: “There are no prodigies in literature. Only in chess, music and math, which have in common the fact that they have nothing to do with life; they don’t feed off life.”

Amis moved to Brooklyn three years ago but has written about America throughout his career, most notably in his non-fiction collections The Moronic Inferno (1986) and The Second Plane (2008), which deals with the post-9/11 experience, and in his 1984 novel Money. “I feel sort of half-American myself. I sometimes believe I can speak American… although I wonder if that’s an illusion.” Thinking more politically: “Anti-Americanism in Europe is almost automatic everywhere… and I could never sympathise with that. After all, it’s based on the only good revolution that’s ever been.” He was not entirely sans reservation, though. “Money has got into too many areas of American life: health, politics… It’s more like an oligarchy that has elections every four years. All the talk now about inequality is tremendously overdue; inequities are built in and almost ossified.” Quoting Saul Bellow, he commented, “It’s the country where, ‘if you’re so smart how come you ain’t rich?’ If I wrote a novel called Money now, God knows what direction it would go in…”

Freeman also asked about Amis’s famous literary friendships. A recent piece in Vanity Fair on the fatwa taken out on Rushdie twenty-five years ago includes a beautiful snapshot of some of them, photographed by Annie Leibovitz, including Rushdie and Ian McEwan. Going back in time, Granta’s 1983 list of the best young British novelists, many of whom have been Amis’s friends, is remarkable for its prescience. Sadly missing today, of course, is the late Christopher Hitchens, who never strayed into fiction. “Ian [McEwan] said it was because he didn’t have the temperament to sit around making things up.” Rereading his final book, Mortality, though, “if transposed into the third person and the past tense, it reads just like a novel slap-bang in the English seriocomic tradition. But, alas, everything in that book is gospel truth.”

And what was in the water when Amis was starting out that gave his generation the heft they turned out to have? “The great energising thing was the sexual revolution… It was of incalculable value to society.” Referring to Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011) on the alleged decline of violence in world history, he pointed out that one of the factors Pinker puts a lot of emphasis on, alongside the state’s expanded monopoly on violence and, flatteringly, the emergence of the novel, is the emancipation of women. “That’s what energised us.”

Looking ahead, Amis’s next novel, The Zone of Interest, will be published by Knopf in September. Like 1991’s Time’s Arrow, it will see him deal directly with the Holocaust. “If you’d asked me [before I wrote Time’s Arrow] who was the least likely British novelist to write about the Holocaust, I’d have said me,” he commented. It went on to become one of his best-reviewed books and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Time’s Arrow is an extraordinary novel because the action happens backwards — not like in the movie Memento, where the scenes are reordered to happen in reverse, but in rewind-motion. “The arrow of time is the arrow of morality,” said Amis, pointing out that, seen in reverse, you can slap a crying child in order to make him stop. The novel’s narrator sees the action in reverse and cannot comprehend its significance; the reader, knowing better, comes to see a well-known horror in a newly terrifying light. The Zone of Interest, which is already one of the most highly anticipated titles on the fall slate, will take a different tack: “it’s social realism of the same period.”

Further reading:

London Fields (1989) is many readers’ favourite Amis novel, a classic in what he calls the “mock heroic style in which we describe low things in a high style”.

Visiting Mrs. Nabokov (1993) is a great introduction to Amis’s non-fiction, and includes great profiles of post-war literary titans J.G. Ballard and Anthony Burgess, amongst others.

Experience (2000) is Amis’s award-winning memoir, though it says as much about Kingsley as it does about Martin. You can read an extract here.