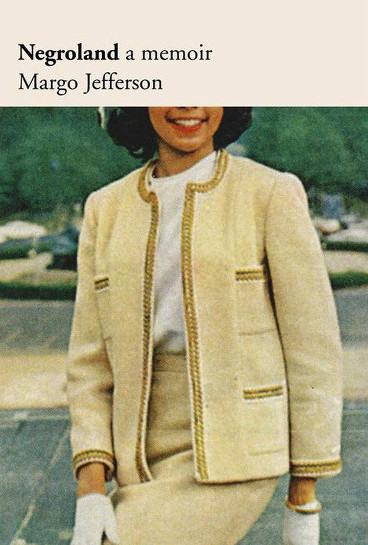

Negroland: A Memoir

Negroland: A Memoir

Margo Jefferson

Pantheon Books, 2015; 256pp

If an authentic life is what you seek, you’re basically doomed to phoniness: this is the paradox that makes “authenticity” one of those words that should only ever appear flanked by inverted commas. The desire to be “authentic” necessitates the sort of reflection that destabilizes both subject and object; neurosis, perhaps despair, that way lies. This is the inciting conundrum in Margo Jefferson’s excellent Negroland, a memoir in name but a project vastly more complex and ambitious in execution.

Jefferson was raised in a well-to-do Chicago family in the 1950s and ’60s, the second daughter of a physician and a social worker-turned-socialite. She learned the piano, she took ballet lessons, she read Little Women and sang Gilbert & Sullivan. In the late ’60s and ’70s, she discovered Black Power and feminism. She became a Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, writing for the New York Times, Newsweek, Vogue. She’s had a Guggenheim Fellowship, she teaches at Columbia, she’s widely revered. Her short book On Michael Jackson, published before the singer’s death, is a luminous, empathetic re-reading of the man and his work.

Yet Jefferson’s also been troubled by doubt, self-hatred, and suicidal thoughts. She’s spent terrible minutes with her head in the oven pledging one day to have the courage to turn it on. At the start of this book, she proclaims herself “often ashamed of what she is, always ashamed of what she lacks”; how, she asks, does someone like this write about herself? “I think it’s too easy,” she goes on, “to recount unhappy memories when you write about yourself… So let me turn back, subdue my individual self, and enter history”.

In entering history, Negroland becomes as much a memoir of a people as it is of a person. Jefferson flits between a “they” and a “we” throughout; social history, as it must, effaces the individual. The black men and women whose lives and actions laid the groundwork for the easier mode of living enjoyed by their descendants fill Jefferson’s pages. Simple biographical sketches suggest the range, diversity, and ambition of African-American achievement before, during, and after Reconstruction. More often, a generalized “they” serves a kind of history-as-timelapse.

After all this historical sweep, we arrive at last at the life of our guide. So where exactly is Negroland?

Negroland is my name for a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty. Children in Negroland were warned that few Negroes enjoyed privilege or plenty and that most whites would be glad to see them returned to indigence, deference, and subservience. Children there were taught that most other Negroes ought to be emulating us when too many of them (out of envy or ignorance) went on in ways that encouraged racial prejudice.

Amateur psychiatrists would say it’s little wonder that Jefferson became a critic, detached as she must have felt in a world where her social class — the aspiring African-American bourgeoisie — left her adrift from both her black and white peers. The need to be distinguished opened up spaces in which anxiety might thrive. “For my generation,” she reports, “the motto was still: Achievement. Vulnerability. Comportment.” Academic success was expected, impeccable manners were mandatory. In addition to one’s behavior, the shape and color of one’s face and the quality of one’s hair played major parts in how one was perceived. “Denise’s skin is burnt sienna,” Jefferson writes of her sister. “Margo and her mother are café au lait, and the blue veins in their hands can be seen by anyone.” These qualities were — for Margo and her mother — genetic passports to the higher echelons of black society. Such access was denied, conversely, to those with noses “broad and flat with wide nostrils” or “dark skin shades like walnut, chocolate brown, black, and black with blue undertones”. In other words, the lighter-skinned you were, the more physiognomically Caucasian, the greater your access to the kind of white-bourgeois life you desired.

Yet the people of Negroland, despite their affluence and cultured ways, lived precarious, contingent lives: “All of you could be designated, at a stroke and for life, vulgar, coarse, and inferior.” Their hard-won privilege could be removed instantaneously; it was merely provisional, unlike the entitlements — the expressions of birthright — of their white peers. “Privilege can be denied, withheld, offered grudgingly and summarily withdrawn. Entitlement is impervious to the kinds of verbs that modify privilege.” Hence how, on vacation in Atlantic City in 1956, the family Jefferson could be snubbed as they were, by a hotel desk clerk who, by relegating them to a lesser room, “turned us into Mr. and Mrs. Negro Nobody with their Negro children from somewhere in Niggerland”.

Yet the people of Negroland, despite their affluence and cultured ways, lived precarious, contingent lives: “All of you could be designated, at a stroke and for life, vulgar, coarse, and inferior.” Their hard-won privilege could be removed instantaneously; it was merely provisional, unlike the entitlements — the expressions of birthright — of their white peers. “Privilege can be denied, withheld, offered grudgingly and summarily withdrawn. Entitlement is impervious to the kinds of verbs that modify privilege.” Hence how, on vacation in Atlantic City in 1956, the family Jefferson could be snubbed as they were, by a hotel desk clerk who, by relegating them to a lesser room, “turned us into Mr. and Mrs. Negro Nobody with their Negro children from somewhere in Niggerland”.

It’s perhaps little wonder that so many tried to “pass” as white. Jefferson’s Uncle Lucious was one, and his success in passing was a revelation to the author:

Now I was in free fall. Who and what are “we Negroes,” when so many of us could be white people? I sat there and reasoned it out: If I am related to Uncle Lucious and I am visibly Negro and Uncle Lucious is invisibly Negro and visibly white… Suddenly the fact of racial slippage overwhelmed me. I was excited for days after. I knew something none of my white school friends knew. It wasn’t just that some of us were as good as them, even when they didn’t know it. Some of us were them.

But Jefferson’s epiphany, when she sees her Uncle Lucious anew, is no match for the weight of social history. Recall Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, whose central figure is a college professor who passes as white for much of his adult life only to be undone by a remark that’s read as a racial slur by one of his students. Coleman Silk’s stubbornness, his tragedy, is born of the same pride that drives the inhabitants of Negroland. He couldn’t face up to the deception he’d perpetrated just as he was unlikely to have achieved so much had he remained true to his racial identity.

You didn’t have to “pass”, though, to face a kind of existential crisis. Because of her relative privilege, Jefferson finds herself “handicapped by race” twice over: “among whites, and among Negroes who found me — let me put it very precisely — socially inept due to an excess of white-derived manners and interests”. By the time the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power were in full swing, she writes, “[t]he entitlements of Negroland were no longer relevant.”

We were not the best that had been known and thought in black life and history. We were a corruption of The Race, a wrongful deviation. We’d let ourselves become tools of oppression in the black community. We’d settled for a desiccated white facsimile and abandoned a vital black culture. Striving to prove we could master the rubric of white civilization that had never for a moment thought we were the best of anything in their life or history.

One of the luxuries never attained, even in Negroland, was “the privilege of freely yielding to depression, of flaunting neurosis as a mark of social and psychic complexity”. (Even today, African-American communities are significantly less likely, statistically, to seek mental health services.) Jefferson, in the 1970s, during her suicidal period, found herself caught between the rock of social history and the hard place of simply being. She is oppressed by having always to consider race: “If I have to talk about RACE and its subdivisions — ethnicity, culture, religion — any more, I will do a Rumpelstiltskin,” runs one monologue. One senses that it’s a subject that’s both terribly interesting and crushingly boring for her; both what shouldn’t matter and what nonetheless does matter. Negroland brilliantly enacts the tension between social and psychological existence in its very structure, as Jefferson sets out to “subdue my individual self, and enter history”. Her own story is thus dwarfed by the governing conflicts and questions of the age, just as every individual is subject to forces that threaten its sovereignty, forces which can make “authentic” living, free from anxiety or contrivance, impossible. This is why, at the end of the book, we see Jefferson returning to her psychotherapist’s each week, still wanting “to dismantle this constructed self of mine”. While one might put Negroland down wanting more of Margo herself, what inches the book towards greatness is the question implicit in its subtitle: for what memoir can be true when written solely from within?

Margo Jefferson will appear at the Seriously Entertaining show It’s Not You at Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater on March 7. This show is now SOLD OUT. Please mark your calendar for the next Seriously Entertaining show, While the Music Lasts, on April 19, when we will be joined by Stephon Alexander, Jon Ronson, Lisa Kron, and Bryan Burrough. Sign up for our mailing list for more details as we announce them.