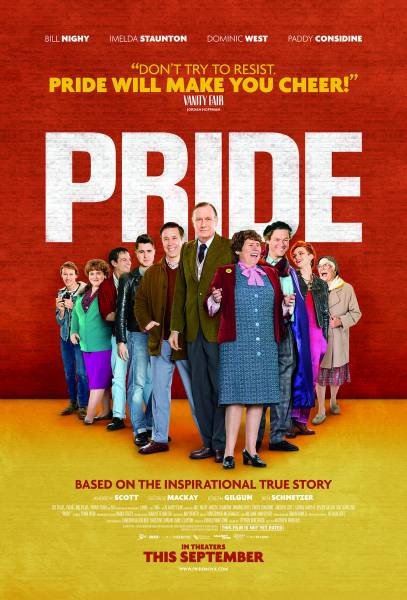

Pride, a great new British movie directed by Matthew Warchus, is as warm and witty as Billy Elliot or Kinky Boots but as fierce as a rampaging Ken Loach.

It’s 1984 and the miners’ strike has begun in opposition to the government’s proposed closure of twenty mines. “One isn’t here to be a softie,” explains then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher in the short montage of archival footage, spliced with shots of picket lines and police vehicles, that begins the film. If you’ll excuse the puns, this is a rich seam of recent British history for TV- and movie-makers, and oft-mined. Billy Elliot covers the same period as Pride, while Brassed Off, set a decade later, examines the aftermath of the unions’ collapse. But Warchus and writer Stephen Beresford have found a totally new angle. Lesbian and Gay Pride, in 1984 in its thirteenth year, is still very much a protest march at this point; a demand for civil rights and tolerance. So it’s extraordinary that a group of lesbian and gay activists should seek to ally themselves with the National Union of Mineworkers. Yet that’s what happened.

Eyes and ears on the ground are provided by Joe (George MacKay), a young man from Bromley just turned twenty, who hops a train to join the marchers at Pride ’84 and falls straight in with a group of activists led by the passionate Mark Ashton (Ben Schnetzer). Mark’s latest idea is to stand shoulder to shoulder with the miners on the basis that an enemy of the government must be a friend of the LGBT community. This is more difficult than he anticipates; many gay activists, alienated by provincial life in industrial towns, had fled to London to escape the monoculture back home. Trade unions are equally resistant to the idea of teaming up with the heavily marginalised gay rights movement. Unperturbed, Mark founds LGSM — Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners — and enlists a handful of dedicated supporters including Gethin (Andrew Scott), Jonathan (Dominic West), Joe, Steph (Faye Marsay), Mike (Joseph Gilgun), Jeff (Freddie Fox), and a newly minted pair “looking for something to do as a couple.” After much ringing around, they eventually find a mining community in South Wales willing to accept their help. This occasions the first great visual gag of the movie, as an elderly woman staggers towards the ringing phone at the mining lodge in Onllwyn so slowly that one is put in mind of Omar Sharif’s entrance in Lawrence of Arabia.

Eyes and ears on the ground are provided by Joe (George MacKay), a young man from Bromley just turned twenty, who hops a train to join the marchers at Pride ’84 and falls straight in with a group of activists led by the passionate Mark Ashton (Ben Schnetzer). Mark’s latest idea is to stand shoulder to shoulder with the miners on the basis that an enemy of the government must be a friend of the LGBT community. This is more difficult than he anticipates; many gay activists, alienated by provincial life in industrial towns, had fled to London to escape the monoculture back home. Trade unions are equally resistant to the idea of teaming up with the heavily marginalised gay rights movement. Unperturbed, Mark founds LGSM — Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners — and enlists a handful of dedicated supporters including Gethin (Andrew Scott), Jonathan (Dominic West), Joe, Steph (Faye Marsay), Mike (Joseph Gilgun), Jeff (Freddie Fox), and a newly minted pair “looking for something to do as a couple.” After much ringing around, they eventually find a mining community in South Wales willing to accept their help. This occasions the first great visual gag of the movie, as an elderly woman staggers towards the ringing phone at the mining lodge in Onllwyn so slowly that one is put in mind of Omar Sharif’s entrance in Lawrence of Arabia.

Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s “Two Tribes,” one of 1984’s biggest hits, plays over an early scene in which Dai (Paddy Considine) takes to the stage at a gay bar to thank the community for their money and help. It’s a powerful moment, itself a meeting of two tribes, that’s later echoed when Mark and the gang arrive in Onllwyn to declare LGSM’s support for the town’s miners. Much of the film’s comedy — and drama — derives from the culture clash between the urbane activists and the conservative miners. Cue Imelda Staunton, on fine furious form, marching across the lodge and insisting that the town’s men “get over there and find a gay or a lesbian right now!” A riotous scene in which Dominic West takes to the dancefloor — ironically to the tune of Shirley & Company’s “Shame Shame Shame” — marks a turning point in relations.

Warchus’s direction is confident and sensitive. His sense of rhythm in particular, honed no doubt during his successful musical-directing career, is superb. Some scenes play out in a single shot, including a marvellous and touching dialogue late on between Bill Nighy and Staunton as the two of them sit making sandwiches. The unspoken is a great British trope, and in Pride the unseen plays a part too. We’re spared the spectacle of a gay-bashing, if not the aftermath — a necessary chunk of grit in a film that occasionally risks being too light. In perhaps the darkest moment of the movie, Mark bumps into an ex, played by Russell Tovey, who murmurs that he’s on his “farewell tour” of the London clubbing scene. Tovey appears out of nowhere, a dead man walking, and is gone almost before his words hit home. In the midst of the hilarity, it’s an unnerving reminder of an issue that, even in 1984, dominated and perverted public perceptions of the gay community.

Mostly, though, Pride is just damn funny. And funny in a characteristically British way. There’s a barnacle-stubborn part of our national character that we love to celebrate, and Pride pretty much hits the bull’s-eye every time. Whether it’s Steph lamenting having her heart broken at a Smiths concert, or one of the group commenting, “How can that be a village? It doesn’t have any vowels!” there’s no mistaking where we are. It doesn’t matter that some of the characters are pretty stock when the writing and performances are this good; you can’t complain while laughing.

Considine, Scott and Marsay stand out, but the breakout performance comes from MacKay as Joe. In order to join LGSM on its first trip to Onllwyn, he tells his parents that he’s going on a residential course to learn how to make choux pastry. When his mother asks him later how it was, his clear-eyed response is heartbreaking: “It was the best experience of my life.” Through his eyes, we see most clearly — and wrenchingly — the tension between the life imagined for him by his family and the life he must lead to be true to himself.

Pride is a timely movie, with the first same-sex marriages taking place in the UK this year and the tide of public opinion turning in the US. It opened well back home last week and goes on limited release in the US on September 26. See it if you can and spread the word; it’s hard to imagine a more consistently entertaining picture emerging in the coming awards season.