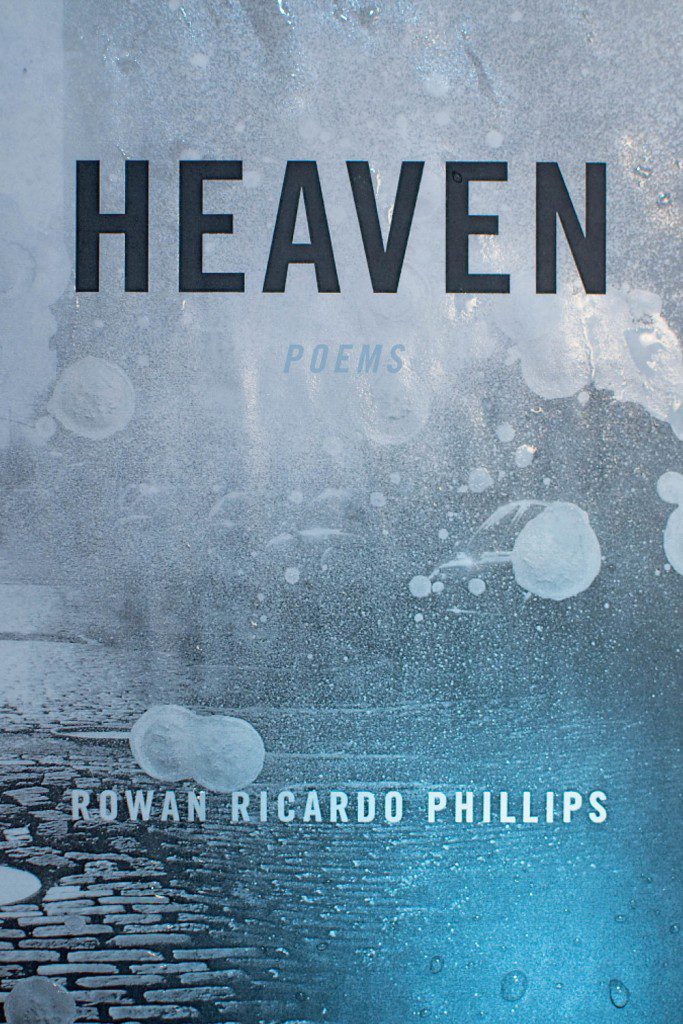

Heaven: Poems

Heaven: Poems

Rowan Ricardo Phillips

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015; 80pp

Heaven, Rowan Ricardo Phillips‘s new collection, dazzles. Nominated last week for the National Book Award, it’s a playful inquiry by an imaginative poet-critic into the nature of capital-H Heaven. While its formal satisfactions derive from its subtle internal symmetries and architectonic qualities, Heaven is also continually surprising, as Phillips’s lexical invention and disruptive perceptions lend each poem a unique flavor. Flitting nimbly between Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare, from Malibu to Colorado, and with a referential field encompassing Mel Gibson, the Wu-Tang Clan, and the stage directions of Cymbeline, it’s a rich reading experience.

“Who the hell’s Heaven is this?” asks Phillips in “The Empyrean”; it’s a question that echoes through the rest of the book. There are gods in Heaven for sure — Zeus, Jupiter, Apollo, the deity of the Old Testament — but there’s also an underlying tension between the notion of Heaven as a place beyond and “heaven” as a function of ekphrastic poetry. In “The Barycenter”, natural beauty becomes a kind of heaven in itself:

Alpenglow ripening the mountain peaks

Into rose-pink pyramids steeped in clouds.

How this light, like a choir of silence,

Queues in the air to sing the snowy mass

To shine, I don’t know.

In physics, the barycenter is the center of mass of two or more objects in its each other’s orbits. Here, a religious Heaven — evoked by pyramids, choir, mass — orbits a vision of natural beauty that one might call heavenly in the context of lyric. At the same time, the physical orbit of the earth around the sun is also described, by day’s transition into night. Hence “the chilled dusk, / Remarkable and rude, runs rouge and glows / As though the blue poem of the Earth desired, / And became, the great rose poem of Heaven”. Heaven here is a “rose poem”, physical beauty transmuted into words. “The Barycenter”, with its overlaid orbits — natural, poetic, and religious — enacts the tensions that underwrite much of the rest of the book.

Just as religion and nature compete for dominion over the concept of Heaven, so too there’s tension throughout between poetry and the natural world. “This night sky won’t always be so Rothko” we are assured in the first of two poems entitled “Mirror For the Mirror”. In “The Beatitudes of Malibu”, the tide is “the Pacific’s not-quite- / Anapestic song of sea and air”. And in perhaps my favorite image in the book, a couple sleeping does so “like the lines of a villanelle: / Apart, together, woven into one.” In each of these moments, art doesn’t quite measure up. The night sky that “won’t always be so Rothko” won’t, in the poem’s second iteration, “always have a meaning”. The sound of the tide isn’t quite anapestic. The sleeping couple can only ever be like the lines of a villanelle; the conceit, though beautiful, is perhaps too poetic. “Is a poem the wonder or the matter?” Phillips asks. Does it matter when the poems are this good?

Just as religion and nature compete for dominion over the concept of Heaven, so too there’s tension throughout between poetry and the natural world. “This night sky won’t always be so Rothko” we are assured in the first of two poems entitled “Mirror For the Mirror”. In “The Beatitudes of Malibu”, the tide is “the Pacific’s not-quite- / Anapestic song of sea and air”. And in perhaps my favorite image in the book, a couple sleeping does so “like the lines of a villanelle: / Apart, together, woven into one.” In each of these moments, art doesn’t quite measure up. The night sky that “won’t always be so Rothko” won’t, in the poem’s second iteration, “always have a meaning”. The sound of the tide isn’t quite anapestic. The sleeping couple can only ever be like the lines of a villanelle; the conceit, though beautiful, is perhaps too poetic. “Is a poem the wonder or the matter?” Phillips asks. Does it matter when the poems are this good?

All these concerns coalesce in “Measure for Measure”, which you can read in full on the New Yorker website or listen to Phillips himself reading here. At the start of the poem, the poet falls asleep while reading Shakespeare’s play, right at the moment when the Duke of Vienna sentences his deputy, Angelo, to death as punishment for executing a young man whose sister the Duke has fallen in love with. (The young man in question is not really dead, though only the Duke knows this.) After some musing on the substance of the play and the meaning of Angelo’s death sentence (later commuted), Phillips returns to the physical world (“My neck aches. / All of Shakespeare feels like lead on my chest”) and looks out the window, where he beholds “A herd of a hundred elk, surviving / The snow as they know how — being elk”. The idea of some kind of ordained justice and the fiendish complication of Shakespeare’s plot go out of the window with Phillips’s imagination — the elk survive without philosophy, with no concept of retributive justice.

The massive seven-pointer, chin held high

To prevent his thick neck from crashing down,

Hoofs the snow and starts towards me, but then turns

To compass the valley between his horns.

The indifference of this elk to Phillips’s meditations on justice is also the indifference of nature to the dreams of humanity — like, in the words of another poem, “the starry night and its great / Astral ambivalence towards small things”. The elk, holding his chin high to balance out the weight of his antlers, compassing the valley between his horns, takes a very different measure of the world than Phillips does.

With its snowy landscapes and ghosts, its fathers and sons, its mirrors up to nature, it’s another Shakespeare play, Hamlet, that haunts Heaven. One might recall Hamlet’s assertion that there’s nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so; thinking is a catalyst, too, in Phillips’s teleology. This is how (a religious) Heaven becomes, in the words of his second poem, “an excuse for mayhem”, much as it does in the plot of Shakespeare’s play. But Hamlet, in the great soliloquies, also motions towards a different kind of Heaven, one of real transcendence and bliss, one beyond our understanding (“there are more things in heaven and earth…”). The calm that comes over Hamlet at the play’s end — and his final line, “The rest is silence” — rhyme with the “celestial silence” at the end of Heaven. A Heaven external to thought, beyond human perception and the limits of our religions, as large as nature, is the final subject of Phillips’s remarkable collection.

Further reading:

When Blackness Rhymes With Blackness (Dalkey Archive Press, 2010; 150pp), in which Phillips’s critical imagination roams through the history of African-American poetry from Phillis Wheatley to Michael S. Harper, all the while questioning the very concept of an a priori African-American poem.

The Ground (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013; 96pp), Phillips’s first, award-winning collection.

Follow Rowan on Twitter: