MERIWETHER [LEWIS]

Never give up the enormity of this dream. Keep telling the lie. The United States will always be the last undiscovered terrain — even if we have to move the white spaces inside our head. Always hold out the promise that you can find your passage to the west, to whatever it is — love everlasting, bottomless wealth, glory —

JACQUES CORNET

Freedom.

MERIWETHER

That dream must never die.

— John Guare, A Free Man of Color, Act 2

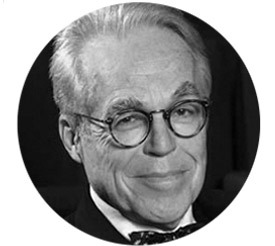

John Guare

These lines, which arrive at the end of one of John Guare’s most recent plays, could be the perfect epigraph for his collected works. Desire for betterment, self-deluding ambition, holding out on a maybe: these unite Guare’s best-known characters, from Artie Shaughnessy in The House of Blue Leaves (1966) and Sally in Atlantic City (1980) to pretty much everyone in Six Degrees of Separation (1990), his most widely performed play. There are plenty of rogues in Guare’s work — con artists, thieves, drug dealers, aspiring terrorists — but they are defined less by their unsavory pursuits than their mastery of self-deception. His is a poetics of delusion.

The House of Blue Leaves, which won the Drama Critics’ Circle Award and the Obie for Best American Play for its 1971 production, was Guare’s breakthrough. Artie Shaughnessy is an aspiring songwriter and actual zookeeper married to the heavily medicated Bananas but having an open affair with the vulgar Bunny Flingus. The play’s action takes place on the day in 1965 when the Pope visited the US to appeal to the UN for an end to the Vietnam War. Artie and Bananas’ son, Ronnie, has absented himself from boot camp to blow up the pontiff at Yankee Stadium. Throw in some riotous nuns and a deaf starlet, bake for two acts, and you have prime Guare: an absurd tableau in garish chiaroscuro brushstrokes.

Artie and Ronnie are the prototypical Guarean dreamers. Ronnie, as a boy, dreamed of playing Huckleberry Finn in the movies — “all the store windows reflected me and the mirror in the tailor shop said, ‘Hello, Huck.'” His failure has evidently weighed on him since, and his disillusionment has led him to the psychotic’s conclusion: only notoriety remains. His father, meanwhile, continues to dream of California and Hollywood, encouraged by the optimistic Bunny. The latter, a marvelous confection, is one of Guare’s many shape-shifters, the embodiment of a specifically American chameleonism that allows her to constantly reinvent herself. “I didn’t work for Con Edison for nothing!” she’ll say, or “I didn’t work in a law office for nix. I could sue you for breach.” Her impossibly extensive resumé is both a good running joke and an indication of the lengths to which she’ll go to keep Artie in line.

The ability to reinvent (or at least deceive) oneself turns out to be something of a running joke throughout Guare’s work. Burt Lancaster’s ageing hood Lou in Atlantic City — a grand, sad film that feels weirdly timely this week — is constantly boasting about the gangsters he’s known (“I knew Bugsy Siegel. I was his cellmate!”). It’s not till nearly the end of the film that he confesses to Sally (Susan Sarandon), the woman he’s fallen in love with, that this is all bluster; that he met Siegel only once, in passing. Sally is a more sympathetic version of Bunny, with dreams of becoming a croupier and travelling the world (“I’m gonna deal my way to Europe”). She’s generally pretty streetwise, but in her romance with Lou ironically overlooks the advice of her croupier-mentor, who warns his trainees, “They have a million different ways of trying to cheat you!” In this scene, as Lou is demystified in front of her, we see the illusions fall away:

In A Free Man of Color (2010), the play’s mixed-race Don Juan, Jacques Cornet, is also a master of reinvention. Repeatedly he retitles his life story to accommodate his changing circumstances: “A Free Man of Color or The Happy Life of a Man in Power. A Free Man of Color or How I Take Control. A Free Man of Color or How Jefferson Is a Liar…” Cornet understands that illusion can be a sustaining force; indeed he relies on it to achieve his many sexual conquests. But by the end of the play, he’s become the victim of one of the grandest of all illusions, the American promise that “All men are created equal.” A Free Man of Color is a burlesque history of the Louisiana Purchase, and as such its theme is the violence at the heart of the nation’s history. The Purchase marked the introduction of racism into the gaudy Eden of New Orleans as the city was sold to the burgeoning Republic by an overstretched Napoleon. As the play ends, Cornet sees clearly — even prophetically. He urges Thomas Jefferson to change the course of history: “You’ll avoid a Civil War — Jim Crow — Dred Scott — lynching — back of the bus — whites only — assassination — degradation — ” He even foresees Hurricane Katrina, “when generations of Margerys and Murmurs and Dr. Toubibs and the girls of Mme. Mandragola will be trapped on rooftops in New Orleans, reaching up to be saved. I say those bitter words ‘Hang on!'” The curtain falls on the final iteration of the play’s title: “A Free Man of Color or How One Man Became an American.”

Nearly two hundred years later, young black men are still being forced to reinvent themselves in order to succeed. In Six Degrees of Separation, con man Paul gulls a series of pretentious Manhattanites, insinuating himself into their lives by pretending to be the son of Sidney Poitier. He learns the shibboleths of their set — Kandinsky, Salinger, Barthelme, pots of jam — and charms cash and a bed for the night out of art dealers Ouisa and Flan Kittredge.

http://youtu.be/ykqgDk_4XG0

But the weight of Paul’s constructed identity is too great. He brings a prostitute into the Kittredges’ home and is thrown out. He seduces a young actor fresh off the bus from Utah, who, unable to face his girlfriend afterwards, commits suicide. His other victims turn on him, too, and their hatred is racially inflected (“My son has no involvements with any black frauds. Doctor, you said something about crack?”) He butts up against the limits of political correctness, white liberal guilt, and collective delusions about the state of the nation. A great comedy of manners, Six Degrees of Separation is also still an urgent and serious work in a nation once again torn apart by racial politics.

Guare’s has been a brilliant career. Earlier this year, he accepted the Dramatists Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award. His tragicomic analysis of the deceptions that sustain us has made for an incomparable contribution to the American stage of the last fifty years. He once wrote that “the only playwrighting rule is that you have to learn your craft so that you can put on stage plays you would like to see.” Fortunately for us, they’re plays we want to see, too.

We’re delighted to be joined by John Guare at our next Seriously Entertaining showcase, Inside the Lie, at City Winery NYC on September 29. You can buy tickets here and copies of Guare’s plays at McNally Jackson. Inside the Lie will also feature Natalie Haynes, Gail Sheehy, Andrew Solomon and Marcelo Gleiser.