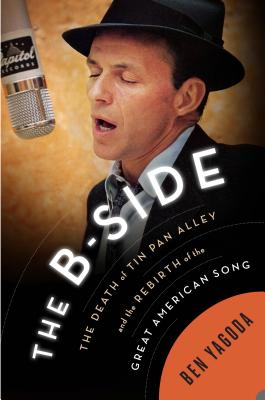

The B-Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song

The B-Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song

by Ben Yagoda

Riverhead Books, 2015; 320pp

“Loesser drew a picture of a train with a caboose and said, ‘This is what makes a good song. The locomotive has to start it. The caboose has to finish it off. Those are the bookends. Then you fill in different colors for the cars in the middle.'”

– Jerry Herman recalls meeting Frank Loesser, in Ben Yagoda’s The B-Side

American songwriting passes from the simple melodies of Tin Pan Alley through the crowning achievements of the Broadway musical to Pet Sounds in Ben Yagoda‘s smashing new book. A detailed study of the evolution of songwriting, The B-Side also offers great insights into America’s changing attitudes towards race, the institutional and industrial factors that shape taste, and how the great American public ditched Gershwin, Porter and Berlin in favor of “(How Much Is) That Doggie In The Window?“

“Nowadays, the consumption of songs in America is as constant as their consumption of shoes,” wrote the New York Times in 1910, “and the demand is similarly met by factory output.” This somewhat depressing assessment of the state of the art at the start of the twentieth century was fortunately not indicative of how things would turn out. Yes, music production would turn into a huge industry — record sales increased by an average of 20 percent each year from 1902 to 1923, by which time more than 40 million were being sold annually, and it kept right on up from there. But the art itself would become increasingly refined over time, absorbing influences and the combined wisdom of an extraordinary confluence of musical geniuses. In the second quarter of the century, when what became known as “The Great American Songbook” was being inscribed into the national consciousness, songwriters produced hundreds of so-called “standards,” most of which are still widely recognized, played, and performed today.

What’s a standard?

Fast or slow, standards are jazz-inflected in rhythm and harmonic possibilities and, especially in later years, show the influence of modern European composers like Ravel and Debussy. The main criterion for songs’ status as standard is the music, but most of them have lyrics that rise to the occasion and are wedded to the melody: sophisticated, once again, and sometimes dazzlingly inventive. The internal rhymes and wordplay from a Cole Porter or Lorenz Hart can suggest W.S. Gilbert with an American accent.

Yagoda’s definition rightly acknowledges the broad palette from which composers like Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, George and Ira Gerswhin, Richard Rodgers, and Porter drew. As he points out, many of the most successful songwriters of the era were Jewish New Yorkers — all but Porter in that last roll call, and even he, according to Rodgers, thought that success lay in writing “Jewish tunes.” Borrowings from Jewish and Yiddish culture can be traced in the syncopation, “gypsy rhythms,” and “bluesy, jazzy harmonies that were beginning to take hold of Americans’ imaginations.” “Syncopation is the soul of every American,” proclaimed Irving Berlin; “pure unadulterated ragtime is the best heart-raiser and worry-banisher that I know.” Ragtime and its immediate descendent jazz originated, of course, in African-American communities, which also had an enormous impact on the course of American songwriting through crossover artists like Mamie Smith, Ethel Waters, and Bessie Smith. And then there were the influences of Polish, Italian, and Irish immigrants… The list could go on and on. In it one can see how the great American experiment — the melting-pot — conspired to transform the course of the popular song.

Ben Yagoda

There were numerous other factors at play. On the technological front, the 78 rpm record dictated for many years the length of a song (four minutes or less). From this a typical verse structure emerged, best typified, Yagoda suggests, by Porter’s “I Get a Kick Out of You,” with its introductory verse and AABA form thereafter. Later, the rise of the 33⅓ rpm LP, whose scope was much larger, played a major part in the preservation of the Songbook in the face of the “rock and roll, novelty numbers, [and] romantic fluff” to be found on singles. Those singles, meanwhile, many of them influenced by the heavily produced and gimmicky style of Mitch Miller at Columbia, were signalling a shift away from the primacy of songwriting towards the production-focused style of later rock music.

History intervened in the form of the Second World War, drastically affecting the record-buying habits of Americans. Suddenly, it was ballads and schmaltz that sold. Life commented, in 1946, “If the songs a country sings are any indication of its mood, the U.S. last week was lolling in an amorous, sentimental daze. On dance floors and radios were heard such plaintive queries as ‘Why don’t you surrender?’ and such pleas as ‘Linger in my arms a little longer, baby.'” By this time, too, the Broadway musical, which is responsible by some accounts for around a third of all great standards, had achieved such heights of sophistication in the integration of music, character, and plot that it was no longer generating the sort of crossover hit that could exist comfortably divorced from its original context. A serious blow had been struck.

By the mid-1950s, in Wilfred Sheed’s phrase, “just like that, the magical coincidence of quality and popularity was over.” Within a decade, though, with the rise of new kinds of songmakers — Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Leiber and Stoller, Carole King, Bob Dylan, Smokey Robinson, Brian Wilson — a new page was being turned in the Songbook. The case continues.

It’s no mean feat to trace cultural trends, which are by their nature misty, intangible. In The B-Side, Yagoda wisely adopts a molecular approach, introducing an enormous cast of characters and demonstrating how their interactions, disputes and collaborations had a sort of butterfly effect on both later songwriters and the industry as a whole. Music-making emerges as a conversational activity, with the Great American Songbook the result of writers sportingly trying to one-up one another. The strength of the canon is of course everywhere evident today, from the critical success of Bob Dylan’s latest album, Shadows in the Night (read Yagoda on Dylan here), to the recent collaborations between Lady Gaga and Tony Bennett. As the pianist Keith Jarrett observes on the very first page of Yagoda’s excellent study, “they are anything but standards by today’s standards.” The standard remains the highest point of aspiration.

You can buy The B-Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song at Barnes and Noble. Ben Yagoda will appear at our next Seriously Entertaining show, No Return, on March 9 at City Winery NYC. Buy your tickets here.