“To remember a person is the most important thing in the novels of Alexandre Dumas,” writes Tom Reiss in the opening pages of his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography The Black Count (Crown, 2012). “The worst sin anyone can commit is to forget.” It’s a sin Reiss cannot be accused of, for The Black Count is above all an act of memorial. Alex Dumas’s life will be unfamiliar to most readers, despite the great fame of his novelist son; in this masterful book, he emerges fully formed in his own right.

The making of The Black Count is the stuff of literary thrillers: obstructive bureaucrats, locked safes, unpublished letters. Arriving in Villers-Cotterêts, the birthplace of Dumas-novelist, Reiss discovers that the curator of the Musée Alexandre Dumas has died, leaving numerous crucial documents in a locked safe. “I am afraid the situation is most delicate,” says Fabrice Dufour, the town’s deputy mayor. “And most unfortunate.” Reiss wines and dines Dufour, trying to persuade him of the potential historical significance of the documents over which he now has jurisdiction. Eventually he gains limited access, finding “seven or eight feet of battered folders, boxes, parchments, and onionskin documents collected over the years”.

According to my agreement with the deputy mayor, I had just two hours to photograph whatever I could; then the policemen standing guard outside would take possession of the safe’s contents and remove it to who knew where, for who knew how long. I took out a camera with a big lens and got to work.

This bit of literary realpolitik brings home the humongous effort involved in producing a work of historical biography. Also the high stakes: without Reiss’s cunning, persistence and fast work, who knows how long it would have been before Dumas’s story came to light with such depth and richness? As it is, his scholarship has already contributed qualitatively and quantitatively to our knowledge of his subject. One only has to compare the Wikipedia page for Thomas-Alexandre Dumas before and after the publication of The Black Count to see the difference.

Alex Dumas, born in 1762, remains the highest-ranking non-white member of a continental European army. This might startle some readers. But like all the best historical biographies, The Black Count is as much a portrait of a time and a place as it is of an individual. And the truth is, France just before and after the revolution was way ahead of its time in its racial mores.

Dumas was born to a lazy-but-cunning father and a slave mother in Saint-Domingue, “the most valuable colony in the world” thanks to its sugar and coffee plantations. As a teenager in 1776, he travelled to France in pursuit of his father, who’d returned a year earlier to lay claim to the family estate.

The young Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie — later simply Alex Dumas — was tall, handsome, and a prodigiously talented swordsman. Moreover, his ethnic background wasn’t the disadvantage one might’ve imagined. Although France was as brutal in the treatment of its slaves as the newly formed US, it was in other ways much more progressive. Louis XIV’s “Code Noir” may have sought to restrict the rights of black slaves but, in placing parameters on their ill treatment, actually allowed many to make a successful legal case for emancipation. In late-eighteenth-century France, many free men proceeded in their careers unimpeded.

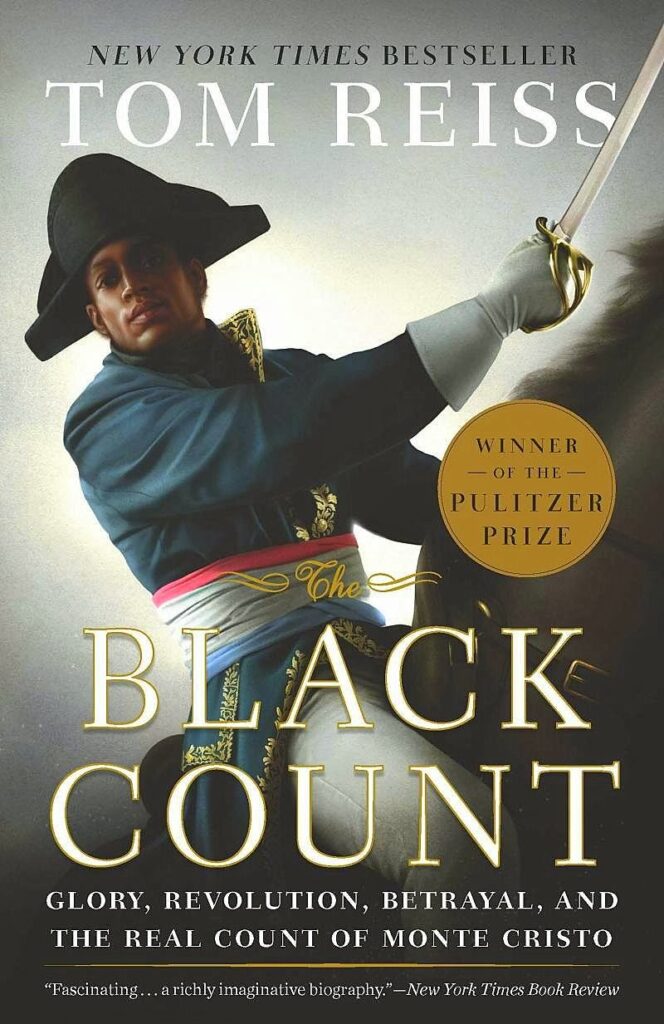

General Dumas in a painting by Olivier Pichat that hangs in the Musée Alexandre Dumas, Villers-Cotterêts.

So it was that Alex Dumas, taking his mother’s name with his army commission, was able to rise as quickly and as far as he did. He signed up before the revolution, survived the schizophrenic bloodshed that accompanied it, and reached the pinnacle of his career in the years after. He was an apt soldier: being outnumbered three to one was “the sort of odds that got Dumas’s blood going”; “the chaos of battle was his home.” His son would later boost his legend in tales that, though surely exaggerated, paint a picture of uncommon physical ability: “More than once he amused himself in the riding-school [manège] by passing under a beam, grabbing it with his arms, and lifting his horse between his legs.”

By the close of 1793, Dumas was in command of the enormous Army of the Alps. In this role his strategic genius became apparent, and although it was a bitter campaign that often brought him into perilous disagreement with the unstable government back in Paris, it paid great reputational dividends:

Until then, his heroics had been a kind of soldiers’ legend: the great horseman with incredible dueling skills and a knack for capturing enemy outposts at the head of a small band of dragoons. It was a legend of the kind of man whom men liked to follow, a warrior’s warrior […] Now, General Dumas had led thousands of soldiers to a great strategic victory, while still facing enemy fire in front of them and risking his life alongside them.

These being the French Revolutionary Wars, Napoleon Bonaparte inevitably emerges as a key antagonist, and Dumas’s destiny is soon intertwined with that of the future emperor. Their opposed philosophies become apparent in their attitudes towards conquered peoples, with Dumas subtly undermining Bonaparte as long as he can. They fight together in Malta and Egypt, in circumstances that would reveal the extent of their difference. Where Dumas protects his troops from suicidal missions in the Alps by strategic avoidance of direct orders, Napoleon is content to lead his army through terrain so inhospitable that many, despairing, commit suicide.

Returning to France from Egypt after the campaign folds, Dumas’s ship starts to take on water and he’s obliged to land in Italy, where he becomes a prisoner of the Holy Faith Army. (His incarceration would later inspire his son’s most celebrated novel, The Count of Monte Cristo.) On his eventual release, his body and spirit broken by the slow poisoning he’s endured at the hands of his captors, he discovers that Napoleon has cut him off. Worse still, Bonaparte has begun to roll back the liberal and anti-slavery policies that had made revolutionary France a rare example of progressive racial attitudes. Within five years Dumas is dead from stomach cancer.

Reiss’s trip to Villers-Cotterêts was not wasted after all.

Even aside from the circumstantial fortunateness that has given us The Black Count, it’s a book full of incidental pleasures. It’s often funny: after the revolution, Reiss writes, “France did not have a normal government: it had a collection of caffeinated intellectuals conducting passionate nonstop shouting matches in the former royal riding school of the Tuileries Palace.” It’s also wise. Of Jacques-Pierre Brissot, one of the leaders of the Girondist movement, Reiss says that “his main character flaw was that of so many French revolutionaries: a zeal for human rights so self-righteous that it translated into intolerance for the actual human beings around him”. And unintimidated by his grand canvas, Reiss breathes evocative life into Saint-Domingue, revolutionary Paris, the frozen Alps and the Egyptian desert alike.