D ark Sparkler

ark Sparkler

by Amber Tamblyn

Harper Perennial, 2015; 128pp

“It’s not easy to write about your dead peers,” said Amber Tamblyn in an interview with Rachel Simon at Bustle published this week. “I was giving myself a lot of permissions that I normally wouldn’t… and telling myself that’s how I am going to get closer to the story, that’s how I’m going to become one with them. But I can’t write like that. It just made it even darker.” Tamblyn’s third collection of poems, Dark Sparkler, is indeed a rhapsody in black, a threnody for the victims of Hollywood. Some of these women (they’re all women) you might know: Brittany Murphy, Sharon Tate, Marilyn Monroe. Others you probably don’t. As poet Diane di Prima writes in a foreword to the book, “At some point you will begin to get curious… At that point, go to the library or search the Internet for information about any girl/woman you find yourself thinking about. Look up Peg Entwistle, Bridgette Andersen, Samantha Smith.” This, it seems, is pretty much what Tamblyn did. In eight black pages in the epilogue (the book is fabulously designed), we see what appears to be her (re)search history for the book, including (out of sequence; for the full American Psycho effect, you’ll need to buy the book):

Search “Fay DeWitt + murder”

Search “Whitney Houston + drug overdose”

Search “Li Tobler died age 27 + suicide”

Search “Frances Farmer died age 56 + shock therapy + alcoholism + abortion + cancer”

Search “Misty Upham died age 32 + police negligence — the woods”

And finally:

Search “Funny cat videos”

(Because you’d need to, I suppose, after all that.)

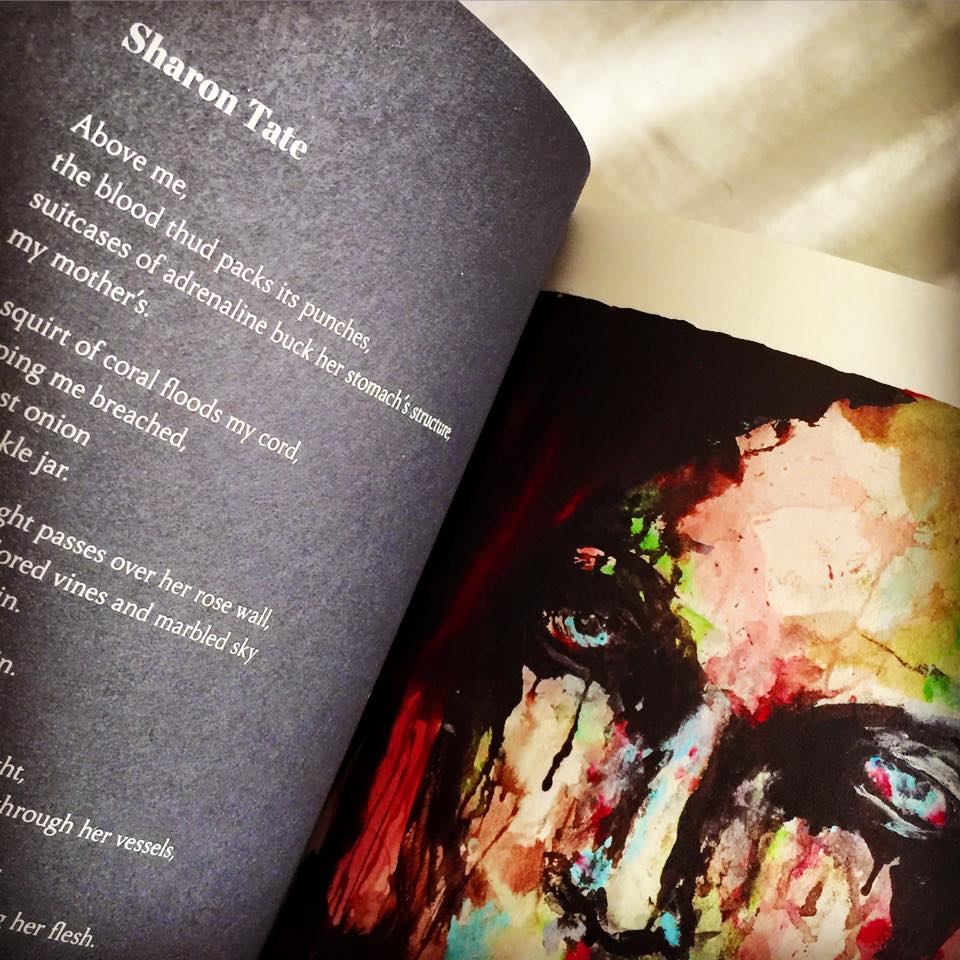

Tamblyn’s poem “Sharon Tate” is accompanied by artwork by Marilyn Manson (Source: Amber Tamblyn / Facebook)

In these poems, Tamblyn exhumes an entire submerged history of female suffering in the movie industry. There are forgotten stars — the Lupe Vélezes and Peg Entwistles of the world, famous principally for their mode of death (in Entwistle’s case, plunging from the “H” of the “Hollywoodland” sign overlooking Los Angeles). But there is just as much mystery surrounding the bigger names. “Brittany Murphy” was the first poem to be written, and the driving force behind the rest of the collection. (You can read it on the Huffington Post website.) In it, we encounter Murphy’s dead body in a series of beautiful-grotesque saccades: “Her body dies like a spider’s. / In the shower, / the blooming flower / seeds a cemetery.” Later: “Her mouth dribbles / onto the bathroom floor. / Pollock blood.” It’s a powerful and painful poem, shot through with deadly double entendres: “The body is lifted from the red carpet,” imagines Tamblyn; later, she comments on “The way she could turn in to her camera close-up / like life depended on her.” For those who don’t remember the details of Murphy’s terrible early death, the line “A pill lodges in the inner pocket of her flesh coat” might suggest suicide or substance abuse. Then di Prima’s instructions send us back to the Internet, where one reads that the official cause of Murphy’s death was initially deferred, then deemed to be pneumonia, and later still an accident. In her notes, Tamblyn points elsewhere: “Update 2014: Cause of death, possible homicide by poisoning.” The truth is unstable, perhaps unknowable.

It seems in some ways that the harder you look the less you see, and this might be Tamblyn’s point. Details blur when probed; motives are a mystery; a suicide is as senseless as a murder is as senseless as an accident. Tamblyn’s gallery of dead stars are left to shine on in their own, unvisited constellation; tragic, unexplained. It would be tasteless to compare Hollywood stars to the schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram, or the murdered aboriginal women in Winnipeg, or the victims of the feminicidio in Ciudad Juárez (the central “event” of Roberto Bolaño’s 2666), or countless other women abused, murdered, or disappeared around the world. But in some ways their narrative fits the same mold. The world turns a blind eye, or forgets, or doesn’t care, even when it’s wrapped up in the very act of surveillance. So it is that an actress might unravel under a withering public gaze, unhelped and unpitied. Tamblyn’s poem “Lindsay Lohan,” which is actually just a title on a blank page, might be made to serve this point exactly (though its wordlessness does leave it rather open to interpretation). In an interview with Vulture, Tamblyn said:

For me, I did not put that in there to say, “You’re next.” I put that in there to say, “I am not going to do [to] you what everyone else does,” which is write a poem about your life — which is not my life. I am not going to project onto your story. I am giving this back to you to write. This belongs to you. Your poem has not been written yet, and it belongs to you. It’s less a statement that she deserves to be grouped in with a bunch of dead women and more of a statement of she deserves to be in there because she is treated like those dead women already; she is treated like she is already dead.

Hollywood stars may have extraordinary mythic power, but they can still be destroyed by the industry-superego. “Untitled Actress” demonstrates how they might be crushed to nothingness in the vanishing point between contradictory specs in a casting call: “Requires an actress that will leave an audience speechless, who’s found her creative voice. / Not a speaking role.” “Heather O’Rourke” calls for a camera push that comes in so close to its subject that she is made to disappear. In “Quentin Dean,” Tamblyn fragments the identity of her subject so many ways that she is scarcely discernible:

Went by the name Andrea.

Was also known as Palmer.

Will be remembered as Dolores.

A.k.a. Corky.

Gave me the nickname Blue Kid.

Is still alive.

Never lived.

Dark Sparkler would be a good companion piece for a screening of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona or the Lynchian diptych of Mulholland Dr. and Inland Empire. It sits alongside The Day of the Locust and Joan Didion’s early work, where the canyons echo with howling. Acting, identity, femininity and tragedy are the four humors in Tamblyn’s poetry. Mixing and remixing them, she has produced a work of brutal, strange beauty. Imagistic in its use of language, formally inventive, and a strong early contender for most stylishly designed book of the year, it manages to be chic, witty, and devastating with each turn of the page.

You can buy Dark Sparkler and Amber’s earlier collections, Bang Ditto (2005) and Free Stallion (2009), at Barnes & Noble. Visit Amber’s website and follow her on Twitter.

Amber Tamblyn will appear at our next Seriously Entertaining show, One Simple Rule, at City Winery NYC on April 21. You can buy tickets here.

Here is the full lineup: