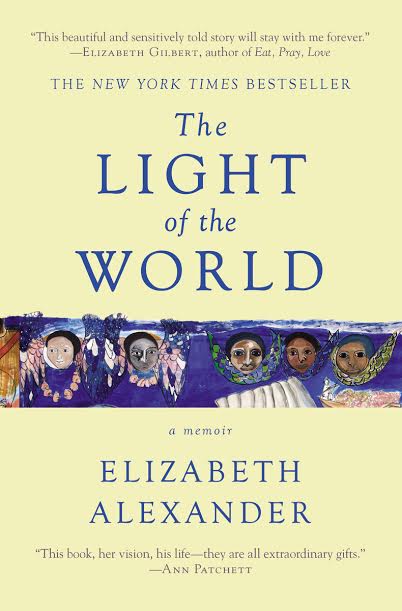

The Light of the World: A Memoir

The Light of the World: A Memoir

Elizabeth Alexander

Grand Central Publishing, 2015; 240pp

Elizabeth Alexander‘s lovely, sad memoir is a tale of two thunderbolts. The first: love at first sight — “A torque inside my stomach, the science of love” — between Alexander and her husband-to-be, the Eritrean artist Ficre Ghebreyesus. The second: Ficre’s sudden death, at the age of fifty, at their home in Connecticut. Alexander’s passage through grief to life on the other side is at once harrowing and hopeful: while her writing eloquently captures the essential terror of death, it also shows how life and literature might be talismans against despair. It’s a book that will stop you in your tracks.

Its fragmentary genesis and structure, which Alexander writes about in an afterword, surely reflect the haphazardness of grief, the slow shape-taking of the narratives we create to make sense of what happens to us. “The story seems to begin with catastrophe,” she writes, “but in fact began earlier and is not a tragedy but rather a love story.” Of course, giving literary shape to life may indeed lend a love story a tragic arc, and so it is here that small details and shared experiences — little regrets, the three dozen lottery ticket Ficre buys two days before his death, a hawk on a branch devouring a squirrel — take on almost mystical weight. These details become part of the fabric of Alexander’s memory, inseparable from the larger events they surround, coloring and seasoning them. They are an ineradicable part of the mystery and mythology of Ficre’s death.

But never does the writing become maudlin. Doubtless it would have been easier to write a book about straight-up grief, a book that worries the moments when Alexander remembers all over again what’s happened (“Ficre not at the kitchen table seems impossible”). Her great achievement, instead, is in transfiguring these moments into something else, something that lands hard in addition to the sadness. Take this passage:

The day he died, the four of us were exactly the same height, just over five foot nine. We’d measured the boys in the pantry doorway the week before. It seemed a perfect symmetry, a whole family the same size but in different shapes. Now the children grow past me and past their father. They seem to grow by the day; they sprout like beanstalks towards the sky.

For sure the sadness is a presence, attached right there to the memory in the first two sentences. But “beanstalks” changes the tone: this is Alexander the parent, not Alexander the bereft. The paragraph falls at the start of a short chapter about the boys at basketball practise. “I watch how they give each other skin for each job well done,” writes Alexander, “this fellowship of beautiful young men, learning to be mighty together inside of this gym with an inspirational woman coach who loves them and is showing them how to be large, skilled, savvy, young men living fully in their physicality after their father’s body so suddenly stopped working.” There’s so much going on in just this sentence: maternal love; sororal admiration; a feeling for the epic in the circle of life; a vitality that’s the very opposite of giving in. Alexander has a visceral sense of how another person might continue, corporeally, in the world after death. They might live on in the bodies of their children, in the physical artefacts they leave behind (Ficre’s art, his paintbrushes), even in the food they might have cooked (recipes are an unexpected but moving feature in the book).

For sure the sadness is a presence, attached right there to the memory in the first two sentences. But “beanstalks” changes the tone: this is Alexander the parent, not Alexander the bereft. The paragraph falls at the start of a short chapter about the boys at basketball practise. “I watch how they give each other skin for each job well done,” writes Alexander, “this fellowship of beautiful young men, learning to be mighty together inside of this gym with an inspirational woman coach who loves them and is showing them how to be large, skilled, savvy, young men living fully in their physicality after their father’s body so suddenly stopped working.” There’s so much going on in just this sentence: maternal love; sororal admiration; a feeling for the epic in the circle of life; a vitality that’s the very opposite of giving in. Alexander has a visceral sense of how another person might continue, corporeally, in the world after death. They might live on in the bodies of their children, in the physical artefacts they leave behind (Ficre’s art, his paintbrushes), even in the food they might have cooked (recipes are an unexpected but moving feature in the book).

The book’s aftertaste is thus not of death but of love. The passages that describe Alexander and Ficre’s courtship are some of the most fabulous. Both partners are taken by the larger, mythic implications of their union: “East and West Africa married, descendant of slaves who survived, descendants of free people of color, descendants of freedom fighters never enslaved, the strongest of all to be conjoined in our children.” But this imaginative engagement with one another as social, historical products is transcended by specificity: the scar on Ficre’s hip, his baldness, their shared taste in music and poetry, the food. “Lifelong insomniac no more”, Alexander almost immediately finds herself in that enviable state of knowledge that marks the safety to be found in love: “the inveterate backseat driver began to fall asleep, safe with him at the wheel.” By the time they’d known each other a week, they’d decided to marry.

Alexander’s primary occupation — (she’s a poet who composed and performed a new poem for President Obama’s first inauguration in 2009) — shines through in the balance and cadences of her prose. It’s also provided her with the tools to demonstrate the great beauty of the love she and her husband shared and how it helped her prepare, however unconsciously, for the awful, unexpected turn her life took. Death is part of life but as such might yet be overruled by life:

When we met those many years ago, I let everything happen to me, and it was beauty. Along the road, more beauty, and fear and struggle, and work, and learning, and joy. I could not have kept Ficre’s death from happening, and from happening to us. It happened; it is part of who we are; it is our beauty and our terror. We must be gleaners from what life has set before us.

If no feeling is final, there is more for me to feel. [my italics]

This is the hope at the end of the tunnel: that comprehension and acceptance might pave the way for love to shine on — undimmed, perhaps even brightened, by death. The beauty Alexander refers to is, in Derek Walcott’s words, “the light of the world”, and it’s this line that provides the words printed on the bench by Ficre’s grave and the title of Alexander’s book. “The poem,” she writes, “says it better than any scripture”.

You can see Elizabeth Alexander at House of SpeakEasy’s Seriously Entertaining event, Razor’s Edge, at Joe’s Pub at The Public Theater on November 1, 2016. Buy tickets here.