Author Tim Teeman (Photo: Juan Bastos)

To create categories is the enslavement of the categorized because the aim of every state is total control over the people who live in it. What better way is there than to categorize according to sex, about which people have so many hang-ups?

— Gore Vidal

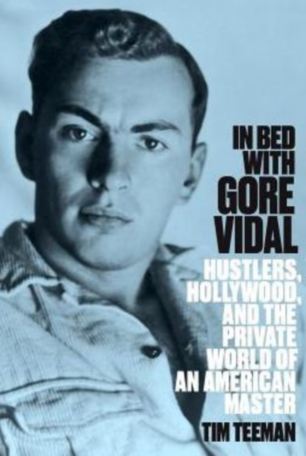

This week I spoke to Tim Teeman about his book In Bed With Gore Vidal: Hustlers, Hollywood, and the Private World of an American Master (Magnus Books, 2013). Gore Vidal was born in 1925, made his name as a novelist in his early twenties, expanded his repertoire to encompass stage and screen, ran for Congress in the Hudson Valley (1960) and California (1982), and made countless friends and enemies in a long life that ended at the age of 86 in 2012. He’s most widely admired as an essayist (start with Selected Essays) and remembered fondly by those with a taste for the showbiz death-match as one of the heavyweights of talk-show controversy.

When Vidal died he left behind him a whole deck of rumours and conflicting testimonies. Much of his work is about sex and sexuality, yet his attitudes towards gay liberation and his own sexuality were full of contradictions. This tension is the starting-point for Tim’s excellent book: “what did Gore Vidal do in bed, how did it shape, or not, his life and work? … In essence — and here imagine the most withering of curled lips from the Master himself — how gay was Gore Vidal?”

Tim speaks to many key figures in Vidal’s life, including actresses Claire Bloom and Susan Sarandon, legendary Hollywood pimp Scotty Bowers, Vidal’s half-sister Nina Straight and nephew Burr Steers, and his staff in his declining years. Using these and many other voices, he builds up a three-dimensional portrait of the writer.

Charles Arrowsmith: A key figure in Vidal’s memoir Palimpsest and your book is Jimmie Trimble, a contemporary of his who was killed at Iwo Jima. Vidal describes Jimmie as the “unfinished business” of his life. What do you think he meant by that?

Tim Teeman: I think he meant, although he would scorn the use of the word, that he loved Jimmie Trimble. What he says took place between them — intense friendship, brief and occasional sex — he attaches a huge importance to in his writing. He likens Jimmie to a missing half. Jimmie, for Vidal, is an ideal of manhood and, later, the ideal of the soldier who American leaders had betrayed. Friends, family and Jimmie’s fiancée all doubted Vidal’s claims on what took place between them, but it was so real and profound for Vidal that it displaced in his writing his relationship of fifty years plus with Howard Austen. Some think deifying Jimmie in the way he does was a narrative trick, endowing Vidal with a tragic romantic nobility, but whatever, every night before bed he would observe Jimmie’s portrait at the top of his stairs.

CA: Vidal famously insisted that “homosexual” and “heterosexual” were fallacious categorisations for people and that most people were more or less bisexual. Is this Vidal the product of his times speaking, or Vidal the farsighted?

TT: If I say both, I do so genuinely, not as a cop-out. Vidal intellectually believed in no fixed categories. He was post-gay years before his time. He was also a product of his generation and times, who, friends and family told me, had a definitely odd attitude towards his own homosexuality. “Fag”, said viciously or dismissively, wasn’t an unknown word to his lips. He didn’t ever campaign for gay rights. AIDS was not a topic he involved himself with, despite having a nephew with the disease who asked him to. But, as I show in the book, just by writing The City and the Pillar in 1948, he knew he had typed himself in some way. He was both proud of that but also frustrated. He ran for office twice and failed both times, he felt his sexuality was an issue both times. He was famously called a “queer” by William F. Buckley on TV. And that itself, as I show in the book, came to generate its own sexual mystery. Gore said he was bisexual, but physically there doesn’t seem to have been much sex with females after he is a young man. He did have very intense relationships with women, which I devote a chapter to in the book. Gore did support sexual liberation and gay organisations. He wrote essays in favor of equality long before others. His sexual radicalism was a constant, but it wasn’t a hobbyhorse. And he didn’t say the thing activists wanted him to say. There’s an amazing interview he did with Larry Kramer, where he doggedly sets out why he’s not interested in joining “the cause”. He didn’t believe in it, but in his own radicalism and the way he stalked the cultural and intellectual stage, he set his own impressive example. In the book, I try to de-tangle this nest of contradictions and puzzles.

Gore Vidal in 2009 (Photo: David Shankbone)

CA: Howard Austen, the man he lived with for fifty-three years until Austen’s death, was sidelined in public — both in Ravello, where locals thought he was Gore’s secretary, and in the US, where Gore maintained that the secret to their lengthy cohabitation was “no sex”. Was this an arrangement that worked for them both?

TT: Yes, it did, although Howard to me seems at least emotionally short-changed in the relationship. Vidal said the key to the longevity of their relationship was that they didn’t have sex; although they had done at the beginning of the relationship. In fact Howard was Gore’s rock. He kept the Vidal roadshow on the tracks. He knew how to temper Vidal’s monstrous ego and piercing words. He could deflate, when necessary, his balloon of pomposity. He also arranged the young male “trade” they had sex with. Howard’s sister told me it was a close and full relationship; her daughter stayed with them in Italy. Howard’s mother would make Gore food to take on tour. On occasion Gore would make it clear how much he loved and depended on Howard. This is made most painfully clear by him totally falling apart after his death in 2003. I should say that Howard would always say how happy he was living his life with Gore. So yes, this was a fifty-three-year relationship and as layered and complex as you might expect such a thing to be. Gore really enjoyed sex, and the book has lots of stories about that, from his night with Jack Kerouac to threesomes with Rock Hudson, and why he was such a proponent of paying for sex.

CA: What role does uncertainty play for the biographer of a subject like Vidal? He claimed that “the instant lie was Truman [Capote]’s art form” but is surely similarly guilty of embroidery and inconsistency if not of outright deception.

TT: I felt I had to be extremely careful. I’m a journalist, so the book relies on interviews and archive material, which was a pleasure to research. I loved meeting his friends and also the family who would speak to me. I am extremely careful not to make any grand claims, but — I hope — bring a lot of fresh material to light and leave room open to interpretation. It is meant to be a very open book, in that sense. This was a complex man with complex attitudes and beliefs and it would ill-befit him to too tightly define or seek to capture Vidal.

CA: When was the Golden Age of Gore? When were the stars best aligned for him?

TT: That’s a lovely question. In my heart I kind of think it was the late 1950s and early 1960s; at this point he’s an intimate of the Kennedys (that will screw up obviously), he’s researching his 1964 book Julian, which will return him to the heart of the literary scene, and he’s in Rome, looking unbelievably hot and having sex with the kind of straight-identifying hustlers he so liked. He’s entertaining in the way he loved to do. The 60s and television was when his fearsome public persona was also being honed.

CA: Thanks, Tim!

Tim Teeman has been a journalist for twenty years. He was editor of The Pink Paper in the UK and has written for The Times of London since 1999. He is also the senior culture editor for The Daily Beast. In Bed With Gore Vidal, which you can purchase at McNally Jackson, is his first book. You can follow Tim on Twitter here.