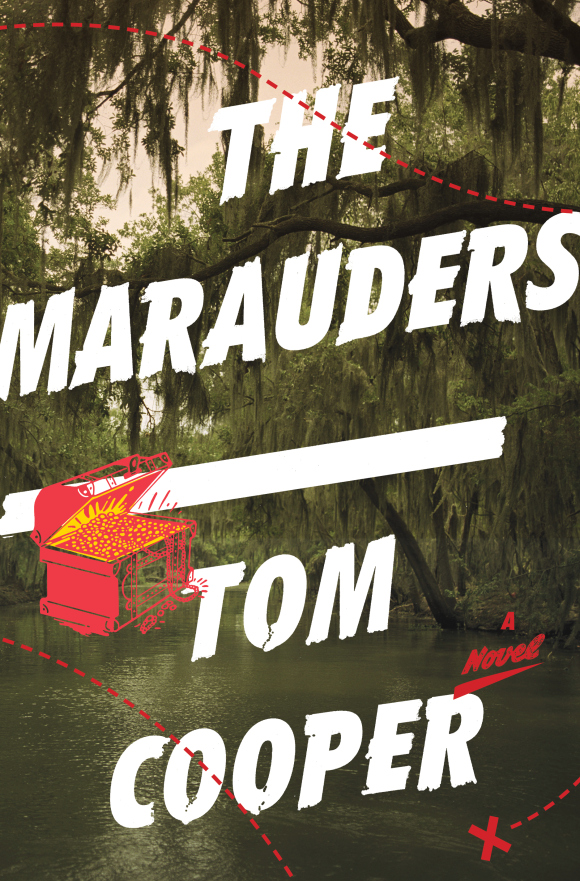

The Marauders

The Marauders

by Tom Cooper

Crown, 2015; 320pp

“Of course he knew that searching for an island of marijuana was crazy. But he also knew that every so often fools stumbled upon fortune, whether by fate or fluke.” This is Cosgrove, one of the gallery of scofflaws and no-hopers that fill out Tom Cooper‘s cracking debut novel, The Marauders. A thriller set in Jeanette, La., in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, The Marauders channel-hops between twin drug dealers, a one-armed shrimper, a teenage boy and his bitter father, a drifter and his criminal buddy, and a BP middleman sent to settle claims to the oil company’s advantage. All the while, its helter-skelter plot unfolds. The teeming swamps of Barataria Bay are a constant mysterious presence, and it’s here that Cosgrove and Hanson, who met on a community-service program, go hunting for the Toup brothers’ legendary marijuana island. It’s also where Lindquist, who pops painkillers from a Donald Duck Pez dispenser, roves with his metal detector, hoping to turn up pirate gold, or, failing that, jewelry lost in the floods of Katrina.

Cooper’s sense of place is masterful, reflecting both the stoicism of the Barataria’s inhabitants and the precariousness of their way of life. It’s a fantastically dangerous place, a place where the cops are forced to pick their battles, alligators are planted in enemy bedrooms, and the working conditions can induce delirium. Yet optimism and enterprise survive — if not unscathed then at least undefeated. Grimes, the BP lawyer, had wanted to leave the Barataria since before he was born but is nobbled for the job to return on the grounds that “Those swamp people will notice a Yankee right away.” Even he can’t help but marvel at the resilience of the swampland:

Amazing the place was still standing. The clapboard houses on creosoted pilings, so jury-rigged they looked ready to topple into the oblivion of the swamp. Same with the makeshift piers, the mud boats and trawling skiffs. Now and then Grimes spotted signs for SWAMP TOURS, some enterprising local who’d slapped a magnetic sign on the side of his boat. Grimes went on these tours against his will during high school field trips. Twenty dollars a head, a guy would take you into the bayou. He’d point out the hummock where escaped slaves once hid from their owners. The man-made hill where a thirty-two-room antebellum mansion once stood before the hurricane of 1915. The place on the horizon where the treasure-laden ships of the pirate Jean Lafitte once sailed.

The swamp’s fecundity and the extreme weather ensure that nothing lasts for long. The Old World — of slavery and of Southern majesty — has been overgrown or blown away. At the book’s outset, and under the shadow of the oil spill, another way of life — shrimping — seems similarly doomed. Restaurants fifteen hundred miles away are putting up signs: “No Gulf shrimp served here.” “Fuck New York,” responds Lindquist, who continues to shrimp with his good arm and an old, hooked prosthetic (someone stole his better arm). Wes Trench and his father, both still mourning the death of Wes’s mother during Hurricane Katrina, struggle by but it’s clear something’s gotta give. Grimes seems to many to offer a solution, with his check-book and unscrupulous approach to timing. But the Baratarians haven’t survived so long without some kind of insane faith in the future and freewheeling, minute-to-minute approach to life. In the book’s closing pages, which depict a small victory for perhaps the most likable character, there is hope yet.

Cooper’s style is very cinematic — the dialogue sparks and cracks like a bonfire — and it’s unsurprising to read that he’s already working up The Marauders for TV. There’s something of the Coen brothers’ work in the hapless criminality of Cosgrove and Hanson, something of Tarantino in the misplaced revenges and explosive violence. The episodic, almost anecdotal structure will be well suited to the screen. But don’t wait to see this on Netflix. The Marauders benefits hugely from Cooper’s verbal dexterity, and it’s a propulsive, highly stimulating read. Whether reviving archaisms (“The noon sunlight pierced through the leaves ceiled overhead”) or coining new usages (“Victor forearmed the sweat from his brow”), Cooper is, in his style, as fertile as the Barataria, as if his language has benefited from the same hydroponic alchemy as the Toup brothers’ weed. On the evidence of his debut, he is the real deal.

Follow Tom Cooper on Twitter: