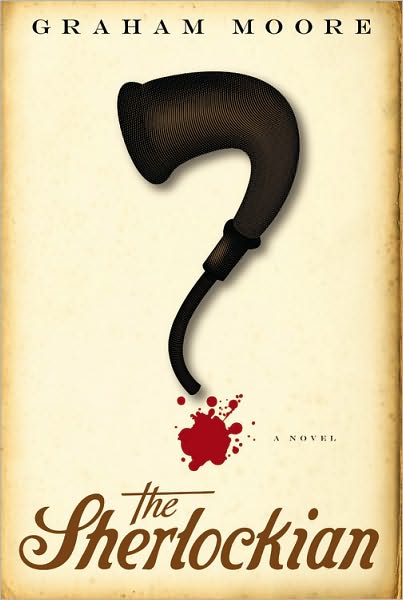

The Sherlockian

The Sherlockian

by Graham Moore

NY: Twelve, 2010; 368pp

Sherlock Holmes, London’s world-famous “consulting detective,” might not have been this popular since his heyday in the late nineteenth century. Robert Downey, Jr., Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller are all currently essaying the sleuth onscreen; Ian McKellen waits in the wings with 2015’s intriguing Mr. Holmes. Graham Moore, who’s about to experience his first major cinematic success with the Alan Turing biopic The Imitation Game, starring Cumberbatch, was one of the first out of the gate in this latest round of Holmesmania with his 2010 novel The Sherlockian. A book for the kinda people who’d take pleasure in noting the erroneous reference to The Sign of Four in the New York Times review (The Sign of the Four, Janet Maslin!), it’s both a clever pastiche and a gripping mystery.

Moore’s inspiration is the question-mark hanging over the lacunae in Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s real-life papers. Upon his death in 1930, it was discovered that a number of unfinished stories, some letters, and an entire volume of his diary were missing. In The Sherlockian, the key document is the diary, which apparently pertains to the last three months of 1900. This is the period during which, not coincidentally, the writer was toying with the resurrection of his most famous creation, whom he’d killed off in the Strand Magazine seven years earlier. What readers wanted to know, when Holmes eventually returned, was what had happened to the great detective while he was gone. What Moore asks is, what happened to Conan Doyle?

A classic image of Holmes and Moriarty locked in mortal combat from the Strand Magazine (1893) by Sidney Paget

In alternate chapters, we watch Conan Doyle as he becomes embroiled in revolutionary feminism, strategic transvestitism, and (inevitably) vile and bloody murder. The rest of the time, we’re following Harold White, the newest inductee in the Baker Street Irregulars, “the world’s preeminent organization devoted to the study of Sherlock Holmes,” as he investigates the present-day murder of one of his fellow Sherlockians. Because it seems, at least initially, that the world is on the verge of discovering what those missing months held for Conan Doyle. Alex Cale, another Irregular, has devoted a sizeable inheritance and a lifetime of searching to unravelling the mystery, and arrives at a convention of Sherlockians in New York at the start of the book to announce his findings. But Cale is not long for this world. Within a few short pages our hero Harold is faced with a conundrum worthy of Holmes himself: a hotel room locked from the inside, a man — Cale — strangled by his own shoelaces, and a single word scrawled in blood on the wall: “ELEMENTARY.” So begins an international search for both Alex’s killer and the missing diary, one which will take Harold all the way to the Reichenbach Falls, where Holmes had himself once seemed to meet his end, locked in mortal combat with Professor Moriarty…

Pleasures abound in The Sherlockian, especially for Holmes fans. Most chapters begin with a choice quote from Conan Doyle’s originals (a reminder of what an elegant stylist he was), while the modern-day sequences are liberally sprinkled with exegetical passages concerning the canon. The bloody word on the wall, for instance, is a reference to A Study in Scarlet. Harold’s encyclopedic knowledge proves critical to following all the elaborate clues Alex’s killer left behind. The Victorian-era passages, meanwhile, are animated by Moore’s humorous pastiches of Doyle’s London — dead “dollymops,” gallows and darbies, elaborate disguises, hansom cabs… Further jest arrives in the form of Bram Stoker — playing Watson to Conan Doyle’s Holmes — whose own literary career in 1900 had faltered at the blood-sucking “Count What’s-His-Name” and a job pandering to Henry Irving at the Lyceum.

Moore’s vision of late-Victorian London is one of a world on the verge of seismic shift. Gloomy gaslight is gradually giving way to the electric bulb, just as Holmes’s brand of detection was lighting the path to modern forensics. Despite the patent horrors of life in 1900 — the lack of universal suffrage, prevalence of prostitution, and so on — one gets the impression that Moore is speaking pretty directly through Harold when he describes the appeal of the early Holmes stories:

“Imagine the scene: It’s pouring rain against a thick window. Outside, on Baker Street, the light from the gas lamps is so weak that it barely reaches the pavement. A fog swirls in the air, and the gas gives it a pale yellow glow. Mystery breeds in every darkened corner, in every darkened room. And a man steps out into that dim, foggy world, and he can tell you the story of your life by the cut of your shirtsleeves. He can shine a light into the dimness, with only his intellect and his tobacco smoke to help him. Now. Tell me that’s not awfully romantic?”

Sherlock Holmes’s ability to rationalise the chaos and violence of life is no doubt a major part of his enduring appeal. “It has long been an axiom of mine,” he says in “A Case of Identity,” “that the little things are infinitely the most important.” If you get the little things straight, all else follows. The notion of a logical world is very attractive. But there may be merit, as Moore seems to suggest in the closing pages of this cartwheeling thriller, to leaving some mysteries unsolved. Can what happened to Conan Doyle in the winter of 1900 really explain the return of Sherlock Holmes? Isn’t it better that such an explanation, if it were truly to exist, go the way of Holmes and Moriarty at the end of “The Final Problem”?

We’re delighted that Graham is one of our Seriously Entertaining guests at No Satisfaction on November 17 at City Winery alongside Ruby Wax, Hooman Majd, Dan Povenmire, and Philip Gourevitch.

Graham Moore published his debut novel, the New York Times best seller The Sherlockian, in 2010. The following year his screenplay The Imitation Game topped the Black List survey of Hollywood’s best unproduced scripts. It was later picked up by the Weinstein Company, which will release the movie on November 28 in the US. The Imitation Game stars Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, the British mathematician and pioneering computer scientist whose work was critical in cracking the Enigma Code for the Allies during the Second World War. Moore is currently working on another novel and recently finished a screen adaptation of Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City.